The PT Expert Security Center first took note of Calypso in March 2019 during threat hunting. Our specialists collected multiple samples of malware used by the group. They have also identified the organizations hit by the attackers, as well as the attackers' C2 servers. The primary goal of the group is theft of confidential data. Main targets are governmental institutions in Brazil, India, Kazakhstan, Russia, Thailand, and Turkey.

Contents

- Calypso APT

- Initial infection vector

- Lateral movement

- Attribution

- Analyzing Calypso RAT malicious code

- Dropper

- Installation BAT script

- Shellcode x86: stager

- Modules

- Commands

- Network code

- Shellcode x64: stager (base backdoor)

- Modules

- Commands

- Network code

- Other options

- Dropper-stager

- Hussar

- Initialization

- Modules

- FlyingDutchman

- Conclusion

- Indicators of compromise

- Network

- File indicators

- Droppers and payload

- Droppers with the same payload

- Payload without dropper

- Hussar

- FlyingDutchman

- MITRE ATT&CK

Calypso APT

The PT Expert Security Center first took note of Calypso in March 2019 during threat hunting. Our specialists collected multiple samples of malware used by the group. They have also identified the organizations hit by the attackers, as well as the attackers' C2 servers.

Our data indicates that the group has been active since at least September 2016. The primary goal of the group is theft of confidential data. Main targets are governmental institutions in Brazil, India, Kazakhstan, Russia, Thailand, and Turkey.

Our data gives reason to believe that the APT group is of Asian origin 1.

Initial infection vector

The attackers accessed the internal network of a compromised organization by using an ASPX web shell. They uploaded the web shell by exploiting a vulnerability or, alternately, guessing default credentials for remote access. We managed to obtain live traffic between the attackers and the web shell.

The traffic indicates the attackers connected from IP address 46.166.129.241. That host contains domain tv.teldcomtv.com, the C2 server for the group's trojan. Therefore the hackers use C2 servers not only to control malware, but also to access hosts on compromised infrastructures.

The attackers used the web shell to upload utilities 2 and malware, 3 execute commands, and distribute malware inside the network. Examples of commands from the traffic are demonstrated in the following screenshot.

Lateral movement

The group performed lateral movement by using the following publicly available utilities and exploits:

- SysInternals

- Nbtscan

- Mimikatz

- ZXPortMap

- TCP Port Scanner

- Netcat

- QuarksPwDump

- WmiExec

- EarthWorm

- OS_Check_445

- DoublePulsar

- EternalBlue

- EternalRomance

On compromised computers, the group stored malware and utilities in either C:\RECYCLER or C:\ProgramData. The first option was used only on computers with Windows XP or Windows Server 2003 with NTFS on drive C.

The attackers spread within the network either by exploiting vulnerability MS17-010 or by using stolen credentials. In one instance, 13 days after the attackers got inside the network, they used DCSync and Mimikatz to obtain the Kerberos ticket of the domain administrator, "passing the ticket" to infect more computers.

Use of such utilities is common for many APT groups. Most of those utilities are legitimate ones used by network administrators. This allows the attackers to stay undetected longer.

Attribution

In one attack, the group used Calypso RAT, PlugX, and the Byeby trojan. Calypso RAT is malware unique to the group and will be analyzed in detail in the text that follows.

PlugX has traditionally been used by many APT groups of Asian origin. Use of PlugX in itself does not point to any particular group, but is overall consistent with an Asian origin.

The Byeby trojan 4 was used in the SongXY malware campaign back in 2017. The version used now is modified from the original. The group involved in the original campaign is also of Asian origin. It performed targeted attacks on defense and government-related targets in Russia and the CIS countries. However, we did not find any clear-cut connection between the two campaigns.

When we analyzed the traffic between the attackers' server and the web shell, we found that the attackers used a non-anonymous proxy server. The X-Forwarded-For header passed the attackers' IP address (36.44.74.47). This address would seem to be genuine (more precisely, the first address in a chain of proxy servers).

The IP address belongs to China Telecom. We believe the attackers could have been careless and set up the proxy server incorrectly, thus disclosing their real IP address. This is the first piece of evidence supporting the Asian origins of the group.

The attackers also left behind a number of system artifacts, plus traces in utility configurations and auxiliary scripts. These are also indicative of the group's origin.

For instance, one of the DoublePulsar configuration files contained external IP address 103.224.82.47, presumably for testing. But all other configuration files contained internal addresses.

This IP address belongs to a Chinese provider, like the one before, and it was most likely left there due to the attackers' carelessness. This constitutes additional evidence of the group's Asian origins.

We also found BAT scripts that launched ZXPortMap and EarthWorm for port forwarding. Inside we found network indicators www.sultris.com and 46.105.227.110.

The domain in question was used for more than just tunneling: it also served as C2 server for the PlugX malware we found on the compromised system. As already mentioned, PlugX is traditionally used by groups of Asian origin, which constitutes yet more evidence.

Therefore we can say that the malware and network infrastructure used all point to the group having an Asian origin.

Analyzing Calypso RAT malicious code

The structure of the malware and the process of installing it on the hosts of a compromised network look as follows:

Dropper

The dropper extracts the payload as an installation BAT script and CAB archive, and saves it to disk. The payload inside the dropper has a magic header that the dropper searches for. The following figure shows an example of the payload structure.

The dropper encrypts and decrypts data with a self-developed algorithm that uses CRC32 as a pseudorandom number generator (PRNG). The algorithm performs arithmetic (addition and subtraction) between the generated data and the data that needs to be encrypted or decrypted.

Now decrypted, the payload is saved to disk at %ALLUSERSPROFILE;\TMP_%d%d, where the last two numbers are replaced by random numbers returned by the rand() function. Depending on the configuration, the CAB archive contains one of three possibilities: a DLL and encrypted shellcode, a DLL with encoded loader in the resources, or an EXE file. We were unable to detect any instances of the last variant.

Installation BAT script

The BAT script is encoded by substitution from a preset dictionary of characters; this dictionary is initialized in a variable in the installation script.

In the decoded script, we can see comments hinting at the main functions of the script:

- REM Goto temp directory & extract file (go to TEMP directory and extract files there)

- REM Uninstall old version (uninstall the old version)

- REM Copy file (copy file)

- REM Run pre-install script (run the installation BAT script)

- REM Create service (create a service launching the malware at system startup)

- REM Create Registry Run (create value in the registry branch for autostart)

At the beginning of each script we can see a set of variables. The script uses these variables to save files, modify services, and modify registry keys.

In one of the oldest samples, compiled in 2016, we found a script containing comments for how to configure each variable.

Shellcode x86: stager

In most of the analyzed samples, the dropper was configured to execute shellcode. The dropper saved the DLL and encrypted shellcode to disk. The shellcode name was always identical to that of the DLL, but had the extension .dll.crt. The shellcode is encrypted with the same algorithm as the payload in the dropper. The shellcode acts as a stager providing the interface for communicating with C2 and for downloading modules. It can communicate with C2 via TCP and SSL. SSL is implemented via the mbed_tls library.

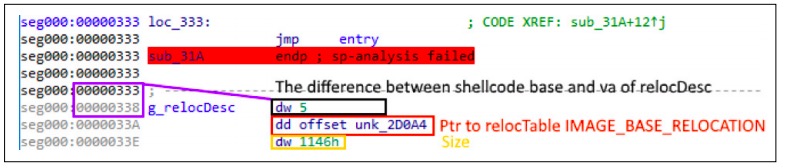

Initial analysis of the shellcode revealed that, in addition to dynamically searching for API functions, it runs one more operation that repeats the process of PE file address relocation. The structure of the relocation table is also identical to that found in the PE file.

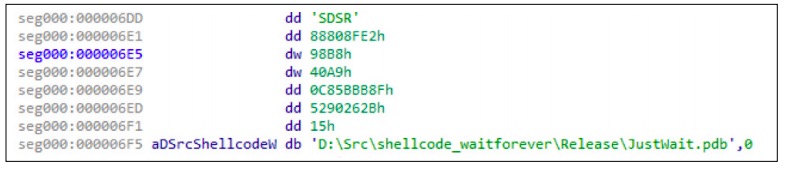

Since the process of shellcode address relocation repeats that of the PE file, we can assume that initially the malware is compiled into a PE file, and then the builder turns it into shellcode. Debugging information found inside the shellcode supports that assumption.

API functions are searched for dynamically and addresses are relocated, after which the configuration hard-coded inside the shellcode is parsed. The configuration contains information about the C2 server address, protocol used, and connection type.

Next the shellcode creates a connection to C2. A random packet header is created and sent to C2. In response the malware receives a network key, saves it, and then uses it every time when communicating with C2. Then the information about the infected computer is collected and sent to C2.

Next three threads are launched. One is a heartbeat sending an empty packet to C2 every 54 seconds. The other processes and executes commands from C2. As for the third thread, we could not figure out its purpose, because the lines implementing its functionality were removed from the code. All we can tell is that this thread was supposed to "wake up" every 54 seconds, just like the first one.

Modules

We have not found any modules so far. But we can understand their functionality by analyzing the code responsible for communication between the shellcode and the modules. Each module is shellcode which is given control over the zero offset of the address. Each module exists in its own separate container. The container is a process with loaded module inside. By default, the process is svchost.exe. When a container is created, it is injected with a small shellcode that causes endless sleep. This is also hard-coded in the main shellcode, and more specifically in JustWait. pdb, most likely.

The module is placed inside with an ordinary writeprocess and is launched either with NtCreateThreadEx or, on pre-Vista operating systems, CreateRemoteThread.

Two pipes are created for each module. One is for transmitting the data from the module to C2; the other for receiving data from C2. Quite likely the modules do not have their own network code and instead use the pipes to communicate with external C2 through the main shellcode.

Each module has a unique ID assigned by C2. Containers are launched in different ways. A container can be launched in a specific session open in the OS or in the same session as the stager. In any particular session, the container is launched by getting the handle for the session token of a logged-in user, and then launching the process as that user.

Commands

The malware we studied can process 12 commands. All of them involve modules in one way or another. Here is a list of all IDs of commands found in the malware, along with those that the malware itself sends in various situations.

Network code

Network communication is initialized after the network key is received from C2. To do that, the malware sends a random sequence of 12 bytes to C2. In response the malware also expects 12 bytes, the zero offset of which must contain the same value (_DWORD) as prior to sending. If the check is successful, four bytes at offset 8 are taken from the response and decrypted with RC4. The key is four bytes sent previously, also located at offset 8. This result is the network key. The key is saved and then used to send data.

All transmitted packets have the following structure.

struct Packet{ struct PacketHeader{ _ DWORD key; _ WORD cmdId; _ WORD szPacketPayload; _ DWORD moduleId; }; _ BYTE [max 0xF000] packetPayload; };

A random four-byte key is generated for each packet. It is later used to encrypt part of the header, starting with the cmdld field. The same key is used to encrypt the packet payload. Encryption uses the RC4 algorithm. The key itself is encrypted by XOR with the network key and saved to the corresponding field of the packet header.

Shellcode x64: stager (base backdoor)

This shellcode is very similar to the previous one, but it deserves a separate description because of differences in its network code and method of launching modules. This shellcode has basic functions for file system interaction which are not available in the shellcode described earlier. Also the configuration format, network code, and network addresses used as C2 by this shellcode are similar to code from a 2018 blog post by NCC Group about a Gh0st RAT variant. However, we did not find a connection to Gh0st RAT.

This variant of the shellcode has only one communication channel, via SSL. The shellcode implements it with two legitimate libraries, libeay32.dll and ssleay32.dll, hard-coded in the shellcode itself.

First the shellcode performs a dynamic search for API functions and loads SSL libraries. The libraries are not saved to disk; they are read from the shellcode and mapped into memory. Next the malware searches the mapped image for the functions it needs to operate.

Then it parses the configuration string, which is also hard-coded in the shellcode. The configuration includes information on addresses of C2 servers and schedule for malware operation.

After that the malware starts its main operating cycle. It checks if the current time matches the malware operational time. If not, the malware sleeps for about 7 minutes and checks again. This happens until the current time is the operational time, and only then does the malware resume operation. Figure 20 demonstrates an example in which the malware remains active at all times on all days of the week.

When the operational time comes, the malware goes down the list of C2 servers specified in the configuration and tries to connect. The malware subsequently interacts with whichever of the C2 servers it is able to successfully connect to first.

Then the malware sends the information on the infected computer (such as computer name, current date, OS version, 32-bit vs. 64-bit OS and CPU, and IP addresses on network interfaces and their MAC addresses). After the information on the infected computer is sent, the malware expects a response from C2. If C2 returns the relevant code, sending is deemed successful and the malware proceeds. If not, the malware goes back to sequentially checking C2 addresses. Next it starts processing incoming commands from C2.

Modules

Each module is a valid MZPE file mapped in the address space of the same process as the shellcode. Also the module can export the GetClassObject symbol, which receives control when run (if required).

Each module has its own descriptor created by a command from C2. The C2 server sends a byte array (0x15) describing the module. The array contains information on the module: whether the module needs to be launched via export, module type (in other words, whether it needs pipes for communicating with C2), module size, entry point RVA (used if there is no flag for launching via export), and module data decryption key. The key is, by and large, the data used to format the actual key.

We should also point out that decryption takes place only if modKey is not equal to the 7AC9h constant hard-coded in the shellcode. This check affects only the decryption process. If modKey does equal the constant, the malware will immediately start loading the module. This means the module is not encrypted.

Each module is launched in a separate thread created specially for that purpose. Launching with pipes looks as follows:

- The malware creates a thread for the module, starts mapping the module, and gives it control inside the newly created thread.

- The malware creates a new connection to the current working C2.

- The malware creates a pipe with the name derived from the following format string: \\.\ pipe\windows@#%02XMon (%02X is replaced by a value that is received from С2 at the same time as the command for launching the module).

- The malware launches two threads passing data from the pipe to C2 and vice versa, using the connection created during the previous step. Two more pipes, \\.\pipe\windows@#%02Xfir and \\.\pipe\windows@#%02Xsec, are created inside the threads. The pipe ending in "fir" is used to pass data from the module to C2. The pipe ending in "sec" is used to pass data and commands from C2 to the modules.

The second thread processing the commands from C2 to the modules has its own handler. This is described in more details in the Commands section. For now we can only say that one of the commands can start a local asynchronous TCP server. That server will accept data from whoever connects to it, send it to C2, and forward it back from C2. It binds to 127.0.0.1 at whichever port it finds available, starting from 5000 and trying possible ports one by one.

Commands

The following is a list of IDs for commands the malware can receive, along with commands the malware itself sends in various situations.

Network code

Each packet has the following structure:

Struct Packet{ Struct Header{ _ DWORD rand _ k1; _ DWORD rand _ k2; _ DWORD rand _ k3; _ DWORD szPaylaod; _ DWORD protoConst; _ DWORD packetId; _ DWORD unk1; _ DWORD packetKey; }; _ BYTE [max 0x2000] packetPayload; };

Each packet has a unique key calculated as szPayload + GetTickCount() % hardcodedConst. This key is saved in the corresponding packetKey header field. It is used to generate another key for encrypting the packet header with RC4 (encryption will not occur without the packetKey field). RC4 key generation is demonstrated in the following figure.

Then yet another RC4 key is generated from the encrypted fields szPayload, packetId, protoConst, and rand_k3. This key is used to encrypt the packet payload.

Next the shellcode forms the HTTP headers and the created packet is sent to C2. In addition, each packet gets its own number, indicated in the URL. Modules may pass their ID, which is used to look up the connection established during module launch. Module ID 0 is reserved for the main connection of the stager.

Other options

As we noted, the dropper may be configured to launch not just shellcode, but executable files too. We found the same dropper-stager but with different payloads: Hussar and FlyingDutchman.

Dropper-stager

The main tasks of this dropper are unpacking and mapping the payload, which is encoded and stored in resources. The dropper also stores encoded configuration data and passes it as a parameter to the payload.

Hussar

In essence Hussar is similar to the shellcodes described earlier. It allows loading modules and collecting basic information about the computer. It can also add itself to the list of authorized applications in Windows Firewall.

Initialization

To start, the malware parses the configuration provided to it by the loader.

Configuration structure is as follows:

Struct RawConfig{ _ DWORD protocolId; _ BYTE c2Strings [0x100]; };

The protocolId field indicates the protocol to be used for communicating with C2. There are a total of three possibilities:

- If protocolId equals 1, a TCP-based protocol will be used.

- If protocolId equals 2, the protocol will be HTTP-based.

- If protocolId equals 3, it will be HTTPS-based.

The time stamp is calculated from the registry from the key SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\ CurrentVersion\Telephony (Perf0 value). If reading the time stamp is impossible, "temp" is added to the computer identifier.

Next Hussar creates a window it will use for processing incoming messages.

Then the malware adds itself to the list of authorized applications in Windows Firewall, using the INetFwMgr COM interface.

To complete initialization, Hussar creates a thread which connects to C2 and periodically polls for commands. The function running in the thread uses the WSAAsyncSelect API to notify the window that actions can be performed with the created connection (socket is "ready for reading," "connected," or "closed").

In general, for transmitting commands, the malware uses the window and Windows messaging mechanism. The window handle is passed to the modules, and the dispatcher has branches not used by the stager, so we can assume that the modules can use the window for communication with C2.

Modules

Each module is an MZPE file loaded into the same address space as the stager. The module must export the GetModuleInfo function, which is called by the stager after image mapping.

FlyingDutchman

The payload provides remote access to the infected computer. It includes functions such as screenshot capture, remote shell, and file system operations. It also allows managing system processes and services. It consists of several modules.

Conclusion

The group has several successful hacks to its credit, but still makes mistakes allowing us to guess its origins. All data given here suggests that the group originates from Asia and uses malware not previously described by anyone. The Byeby trojan links the group to SongXY, encountered by us previously, which was most active in 2017.

We keep monitoring the activities of Calypso closely and expect the group will attack again.

Indicators of compromise

Network

23.227.207.137

45.63.96.120

45.63.114.127

r01.etheraval.com

tc.streleases.com

tv.teldcomtv.com

krgod.qqm8.com

File indicators

Droppers and payload

C9C39045FA14E94618DD631044053824

E24A62D9826869BC4817366800A8805C

F0F5DA1A4490326AA0FC8B54C2D3912D

CB914FC73C67B325F948DD1BF97F5733

6347E42F49A86AFF2DEA7C8BF455A52A

0171E3C76345FEE31B90C44570C75BAD

17E05041730DCD0732E5B296DB16D757

69322703B8EF9D490A20033684C28493

22953384F3D15625D36583C524F3480A

1E765FED294A7AD082169819C95D2C85

C84DF4B2CD0D3E7729210F15112DA7AC

ACAAB4AA4E1EA7CE2F5D044F198F0095

Droppers with the same payload

85CE60B365EDF4BEEBBDD85CC971E84D

1ED72C14C4AAB3B66E830E16EF90B37B

CB914FC73C67B325F948DD1BF97F5733

Payload without dropper

E3E61F30F8A39CD7AA25149D0F8AF5EF

974298EB7E2ADFA019CAE4D1A927AB07

AA1CF5791A60D56F7AE6DA9BB1E7F01E

05F472A9D926F4C8A0A372E1A7193998

0D532484193B8B098D7EB14319CEFCD3

E1A578A069B1910A25C95E2D9450C710

2807236C2D905A0675878E530ED8B1F8

847B5A145330229CE149788F5E221805

D1A1166BEC950C75B65FDC7361DCDC63

CCE8C8EE42FEAED68E9623185C3F7FE4

Hussar

43B7D48D4B2AFD7CF8D4BD0804D62E8B

617D588ECCD942F243FFA8CB13679D9C

FlyingDutchman

5199EF9D086C97732D97EDDEF56591EC

06C1D7BF234CE99BB14639C194B3B318

MITRE ATT&CK

- See the section "Attribution."

- See the section "Lateral movement."

- See the section "Analyzing Calypso RAT malicious code."

- unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/unit42-threat-actors-target-government-belarus-using-cmstar-trojan/

- nccgroup.trust/uk/about-us/newsroom-and-events/blogs/2018/april/decoding-network-data-from-a-gh0st-rat-variant/