The Threat Intelligence team at the Positive Technologies Expert Security Center has been keeping a close eye on the TA505 cybercrime group for the last six months. The malefactors are drawn towards finance, with targets scattered in dozens of countries on multiple continents.

What is TA505 famous for?

The cybergang has been quite prolific since 2014: their arsenal includes the Dridex banking trojan, Neutrino botnet, as well as Locky, Jaff, GlobeImposter, and other ransomware.

The group's attacks have been detected all around the world, from North America to Central Asia.

Despite being mainly motivated by profit, in the past six months they have also attacked research institutes, energy companies, healthcare institutions, airlines, and even government agencies.

Below is an example of a phishing message containing malware developed by the group. Judging by the email address, the attack targeted the British Foreign Office.

The group has been using the FlawedAmmyy remote access tool since spring 2018 and the new ServHelper backdoor since the end of 2018. TA505 is among the few groups that can boast of continuous activity over a long timeframe. Moreover, each new wave of attacks shows interesting changes in the group's tools.

Such a high clip of attacks cannot stay invisible: our colleagues at companies including Proofpoint, Trend Micro, and Yoroi have already reported on the techniques and malicious software used by TA505. However, many intriguing issues still remain unaddressed:

- The PE packer unique to the group

- A version of the ServHelper backdoor that, instead of custom-developed functionality, relies on NetsupportManager remote control software

- Network infrastructure: registrars and hosting providers, including overlap with infrastructure of the Buhtrap group

- Other malware used by the group not covered previously

This is the first article of a series about the TA505 group.

Part 1. In the beginning was the packer

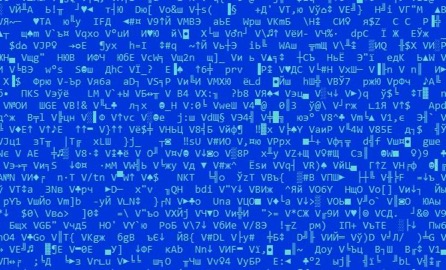

In mid-June 2019, we saw new variants of FlawedAmmy malware loaders with significant changes from previous versions. For example, the visual representation of code in hexadecimal was different. This pattern became a common theme in several samples that we analyzed.

Quick analysis showed that we were looking at an unknown packer of executable files. Later we found that this packer was used not only for the loaders in question, but for other TA505 malware, including payload. We decided to explore the unpacking logic in order to be able to automatically extract the contents.

Layer 1. Tricky XOR

The key portion of the unpacker is preceded by a large number of junk instructions. Malware developers often use this technique to evade antivirus emulators. The interesting part starts when 0xD20 of buffer memory is allocated using the WinAPI function VirtualAllocEx. Memory is allocated with PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE rights, which allow writing and executing code.

The data section of the file contains an array. The contents of the array are decoded and the result is written to the allocated memory. Here is the decoding process:

- Interpret 4 bytes as integer.

- Subtract the order number of the byte in the sequence.

- Perform XOR with a set constant.

- Perform a circular shift to the left by 7 positions.

- Perform XOR with set constant again.

We'll call the algorithm SUB-XOR-ROL7-XOR when referring to it later.

Decoding is followed by sequential initialization of variables. This can be represented as declaring a C struct in the following format:

struct ZOZ {

HMODULE hkernel32;

void *aEncodedBlob;

unsigned int nEncodedBlobSize;

unsigned int nBlobMagic;

unsigned int nBlobSize;

};

in which:

- hkernel32 describes the library kernel32.dll.

- aEncodedBlob is a pointer to the encoded block of data we were talking about when noting the visual similarity of the samples.

- nEncodedBlobSize is the 4-byte size of the encoded data block.

- nBlobMagic is a 4-byte constant ahead of the data block, to which we will return later on.

- nBlobSize is the 4-byte size of the decoded data block.

We called the struct ZOZ (or "505" in l33t speak).

Code execution jumps to the decoded buffer (removing any doubt that the now-decoded data consists of executable code) and a pointer to the populated struct is passed in a function argument:

Layer 2. Less is more

Once the portion of code is decoded and run, it starts gathering addresses of the WinAPI functions GetProcAddress, VirtualQuery, VirtualAlloc, VirtualProtect, VirtualFree, and LoadLibraryA. These functions are often used with shellcodes, in order to groom memory to run the payload.

When everything is ready, the encoded data block is passed and then "slimmed down." The first two of each five bytes are discarded and the remaining three are kept:

Then starts the decoding, which we have called SUB-XOR-ROL7-XOR. To perform XOR, the nBlobMagic value passed in ZOZ is used as a constant.

After that, the resulting array is passed to a function in which more complicated transformations take place. Judging by the characteristic constant values, we can easily identify a popular FSG (Fast Small Good) PE packer. Curiously enough, the original FSG packer version compresses PE by sections, whereas in our case the algorithm works with the PE as-is.

At this stage, the memory contains the unpacked PE file ready for further analysis. The remaining part of the shellcode will overwrite the original PE in the address space with the unpacked version and will then run it correctly. Interestingly, during modification of the module entry point, there are manipulations involving PEB structures. We do not know why the attackers decided to forward the kernel32 descriptor from the first-layer logic instead of getting it with the help of the same PEB structures.

Conclusion

The payload is unpacked as follows:

- Decode shellcode with SUB-XOR-ROL7-XOR.

- Populate the ZOZ struct and call the shellcode.

- Slim payload (five to three).

- Decode payload with SUB-XOR-ROL7-XOR.

- Decompress with FSG packer.

As the malware evolved, so did its logic: the SUB-XOR-ROL7-XOR circular shift (in our case, by seven positions) has been changed to five and nine positions and an x64 packer version was released, among other changes. The cybergang's "calling card" packer is an excellent start to a series of upcoming tales about TA505 tools and techniques.

In future articles, we will discuss how the group's tools have changed during recent attacks and how its participants have interacted with other cybergroups. We will also explore malware samples not covered before.

Authors: Alexey Vishnyakov and Stanislav Rakovsky, Positive Technologies

IOCs

b635c11efdf4dc2119fa002f73a9df7b (packed FlawedAmmyy loader)

71b183a44f755ca170fc2e29b05b64d5 (unpacked FlawedAmmyy loader)