Malware is one of the main tools of any hacking group. Depending on the level of qualification and the specifics of operation, hackers can use both publicly available tools (such as the Cobalt Strike framework) and their own developments.

Creating a unique set of tools for each attack requires huge resources; therefore, hackers tend to reuse malware in different operations and also share it with other groups. The mass use of the same tool inevitably leads to its getting on the radar of antivirus companies, which, as a result, reduces its efficiency.

To prevent it from happening, hackers use code packing, encryption, and mutation techniques. Such techniques can often be handled by separate tools called crypters or sometimes simply packers. In this article, we will use the example of the RTM banking trojan to discuss which packers attackers can use, how they complicate detection of the malware, and what other malware they can pack.

Packer-as-a-service

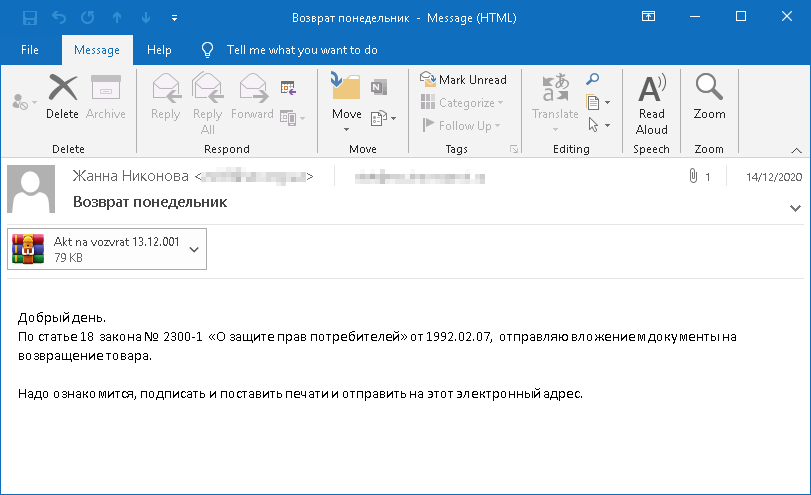

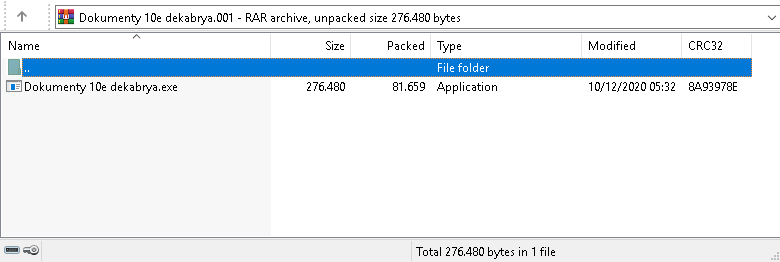

A hacker group responsible for RTM distribution regularly sent mass phishing emails with malicious attachments until the end of 2020. Apparently, the attacks were automated.

Each attachment contained files that significantly differed from each other, but the final payload remained almost the same.

Such feature is a natural consequence of using crypters. Initially, the group behind RTM used its own unique crypter. In 2020, however, the group changed it twice.

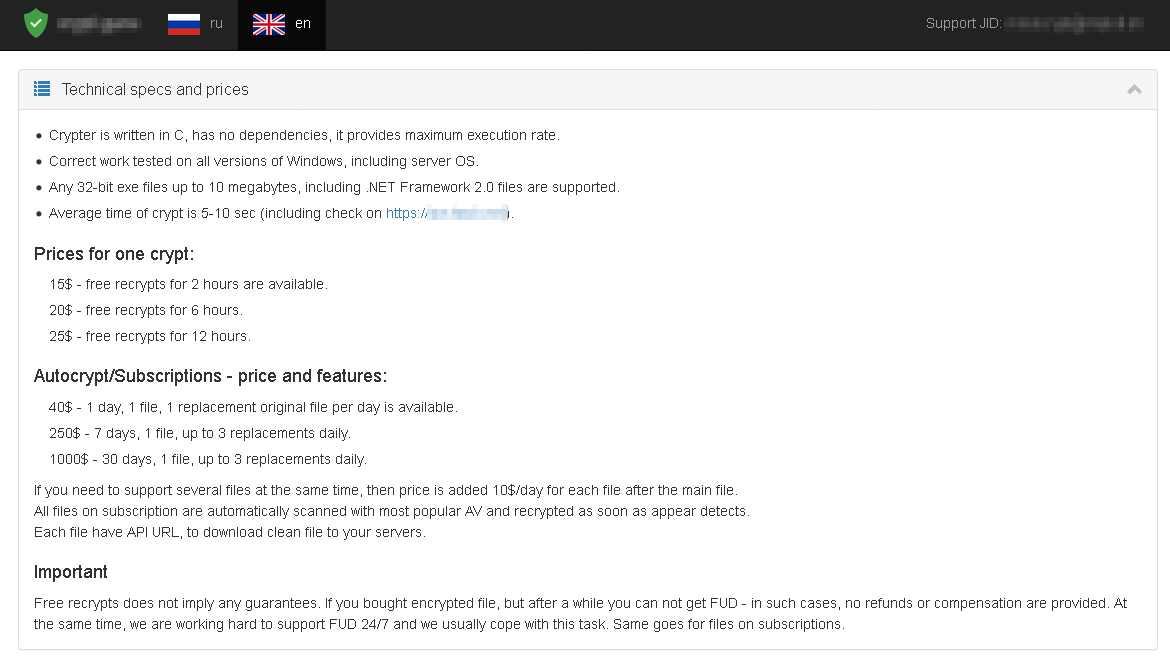

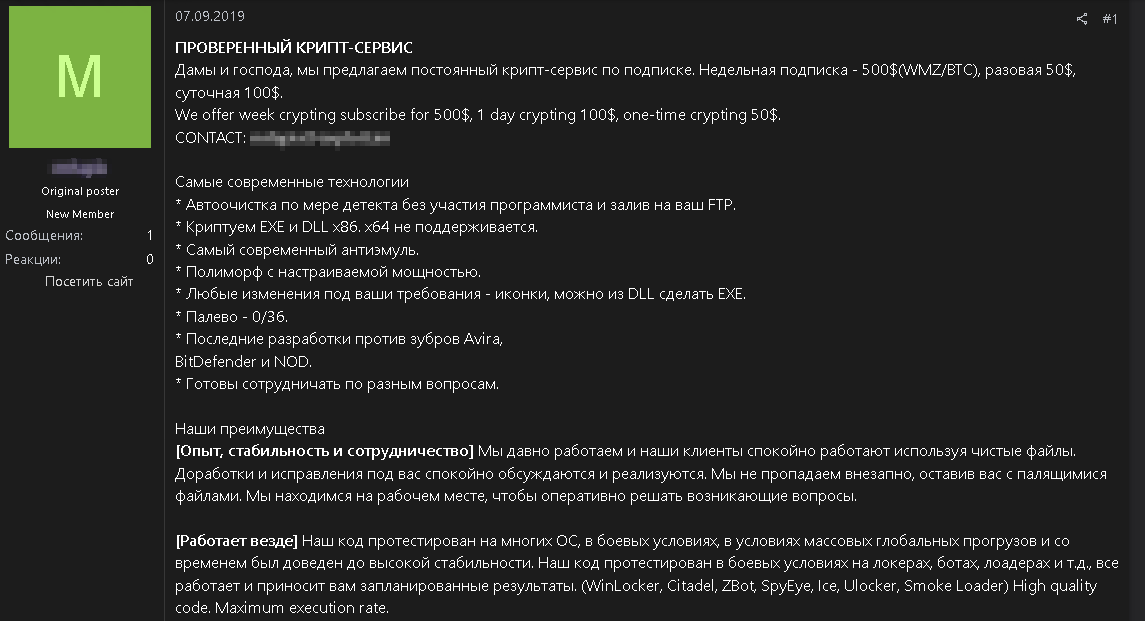

When analyzing samples packed in a new way, we detected numerous other malware protected by similar method. Taking into account the fact that packing process is automated, such overlapping with other malware allows us to assume that attackers use the packer-as-a-service model. In this model, packing of malicious files is delegated to a special service managed by a third party.

Access to such services can often be found on sale on hacker forums.

Later in this article, we will discuss specific examples of crypters used by the RTM group.

Rex3Packer

The first use of this packer by the RTM group that we detected dates back to November 2019. The group started actively using the packer in April–May 2020. Rare uses of the packer for distributing old versions of the RTM trojan were also observed in late January 2021.

We couldn't associate this packer with any of the publicly described ones, so we named it according to three specifics of its working: recursion, bit reverse, and reflective loading of PE files (reflection), hence the name Rex3Packer.

Unpacking algorithm

The overall algorithm for extracting the payload is as follows:

- A predetermined amount of memory is allocated with read, write, and execute rights using VirtualAlloc.

- The content of the current process image in the memory is copied to the allocated buffer (in particular, section .text).

- Control passes to the function inside the buffer.

- The difference is calculated between the location of data in the buffer and in the PE file image (difference between the addresses in the buffer and virtual addresses in the image). This difference is written to the ebx register. All references to virtual addresses in code are indexed by the content of this register. As a result, wherever necessary, a correction is added to the PE image addresses that allows obtaining the corresponding address in the buffer.

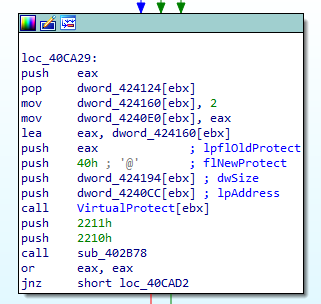

Figure 6. Calls to functions and variables taking into account the correction in the ebx register - Another buffer is allocated for packed data.

- By calling VirtualProtect, RWX rights are assigned to the entire memory region with the PE file image.

- The packed data is copied to the buffer.

- The packed data is decoded.

- The memory region with the PE image is filled with null bytes.

- The decoded data represents an executable file—the PE payload. This payload is reflectively loaded to where the initial PE image was, and control passes to its entry point.

A specific algorithm for decoding packed data is of special interest to us. In this case, it would be incorrect to compare packing with compression, as the algorithm is such that the size of packed data is always bigger than that of the initial data.

The packed data is preceded by a 16-byte header that contains four 4-byte fields:

- Size of the header

- Size of initial data (PE payload)

- Position in initial data (*) at which they are divided (more details below)

- Encoding mode (1, 2, or 4)

The decoding looks as follows:

- Inside each byte, bit order is reversed (for example, 10011000 becomes 00011001).

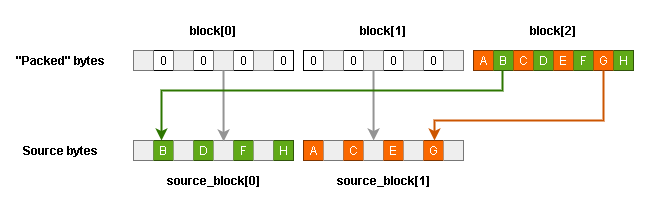

- Depending on encoding mode (1, 2, 4), data is divided into blocks with N size of 9, 5, or 3 bytes, respectively. The result of the block decoding is N-1 byte (8, 4, or 2).

- In the first N-1 bytes of the block, some bits are missing: their values always equal zero. To restore the original bytes, the missing bits are extracted from the last byte of the block by using 00000001, 00010001, or 01010101 masks. The mask is shifted for each subsequent byte. As a result, the last byte of the block is composed of the bits extracted from previous bytes and united by the logical operation OR.

For example, in mode 4, the last byte is composed of even bits of the block's first byte and odd bits of the block's second byte. As a result of "returning" these bits to the first and second bytes, an original sequence of two bytes is composed.

Figure 7. Scheme of obtaining initial bytes in mode 4 - When bits are restored in all blocks, the obtained data represents the initial PE file divided by two parts at position (*). These parts, in turn, were swapped. The second rearrangement (taking into account the (*) value) allows obtaining the original file.

Obfuscation

To complicate code analysis, various obfuscation techniques are used in the packer:

-

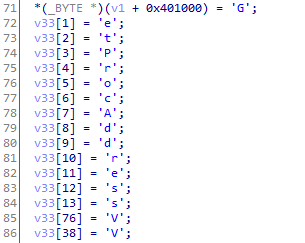

In between the execution of significant code, various WinAPI functions are called. Their results are saved but not used, and the functions are selected so that not to affect the program operation.

Figure 8. Calling WinAPI functions

-

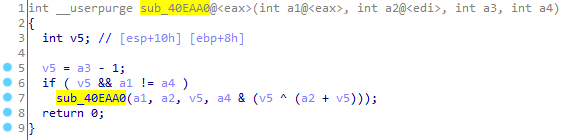

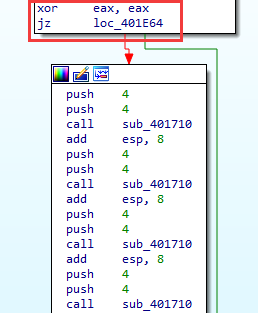

A typical feature of this packer is the presence of cycles (not performing useful operations) implemented via a recursive function.

Figure 9. Recursive function (sample without junk code)

-

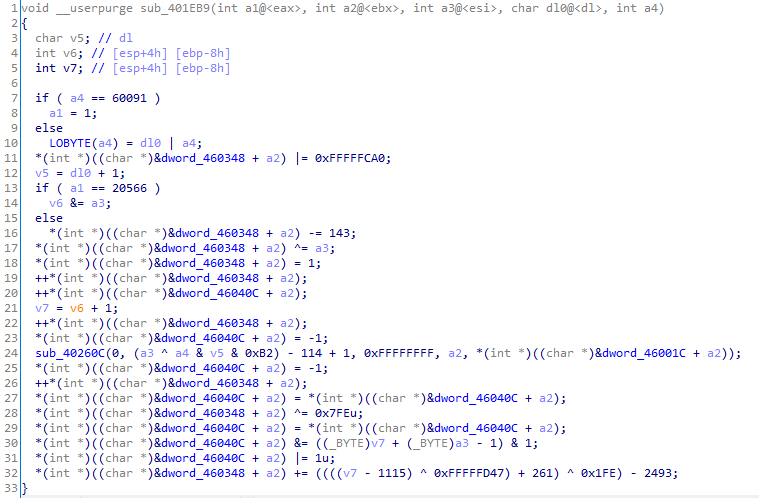

For further obfuscation, several dozens of randomly generated functions are added to executable file. They may call each other, but none of them obtains control ever.

Figure 10. Example of generated function

Usage

In addition to RTM samples, we detected the use of Rex3Packer for packing various malware, mainly originating from the CIS countries. Below is the list with examples of such malware:

| Malware family | SHA256 |

|---|---|

| Phobos Ransomware | 6e9c9b72d1bdb993184c7aa05d961e706a57b3becf151ca4f883a80a07fdd955 |

| Zeppelin Ransomware | 8d44fdbedd0ec9ae59fad78bdb12d15d6903470eb1046b45c227193b233adda6 |

| Raccoon Stealer | 3be91458baa365febafb6b33283b9e1d7e53291de9fec9d3050cd32d98b7a039 |

| KPOT Stealer | 9b6af2502547bbf9a64ccfb8889ee25566322da38e9e0ccb86b0e6131a67df1e |

| Predator The Thief | d1060835793f01d1e137ad92e4e38ef2596f20b26da3d12abcc8372158764a8f |

| QakBot | 18cc92453936d1267e790c489c419802403bb9544275b4a18f3472d2fe6f5dea |

We also detected the use of this packer for packing malware samples of the Nemty, Pony, and Amadey families. This is, of course, not an exhaustive list of all cases of using Rex3Packer.

HellowinPacker

In May 2020, RTM started using a new packer and went on using it until the beginning of 2021. We called it HellowinPacker because of the file name "hellowin.wav" we spotted in strings of some samples.

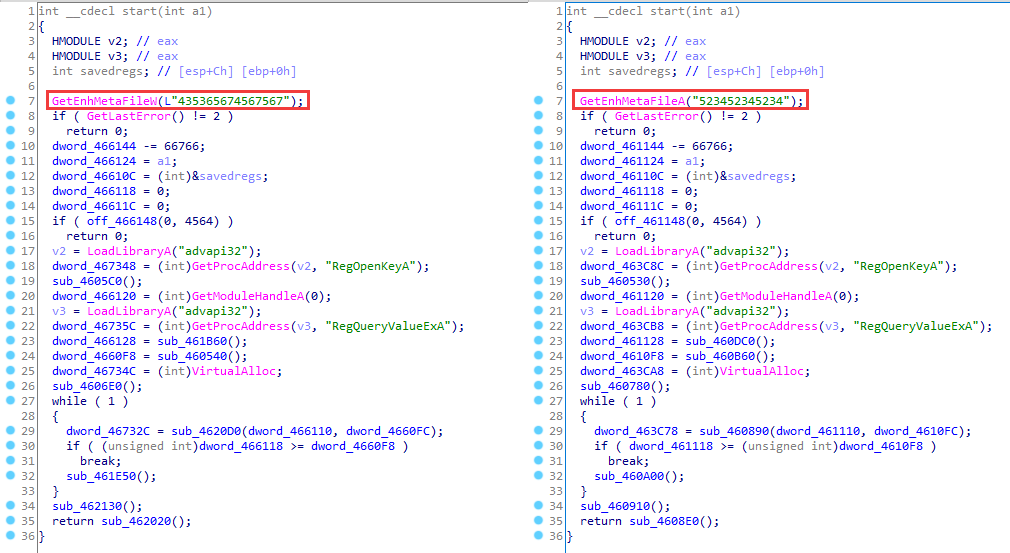

The packer's key feature is two levels of code mutation. The first one significantly changes the unpacking code structure, making samples look different from each other.

The example above shows the comparison of samples 5b5f30f7cbd6343efd409f727e656a7039bff007be73a04827cce2277d873aa0 (on the left) and 1f9a8b3c060c2940a81442c9d9c9e36c31ad37aaa7cd61e1d7aec2d86fe1c585 (on the right).

The second level only changes some details, and the code structure remains in general the same. The changes mainly affect assembler instructions and constants that do not impact the program operation. As a result, the code looks almost identical when decompiled.

Just like Rex3Packer, HellowinPacker is actively used by attackers to pack various malware. Note that malware from the same family has the same structure when packed. This lasts for at least some time, after which the structure can change.

All these features coincide with the description of a packing service the access to which is sold on hacker forums:

Apparently, each unique crypter has its own structure of generated code. The crypter itself can also mutate code but at a lower level, without changing the program structure. In any case, the significant executable code remains the same.

Unpacking algorithm

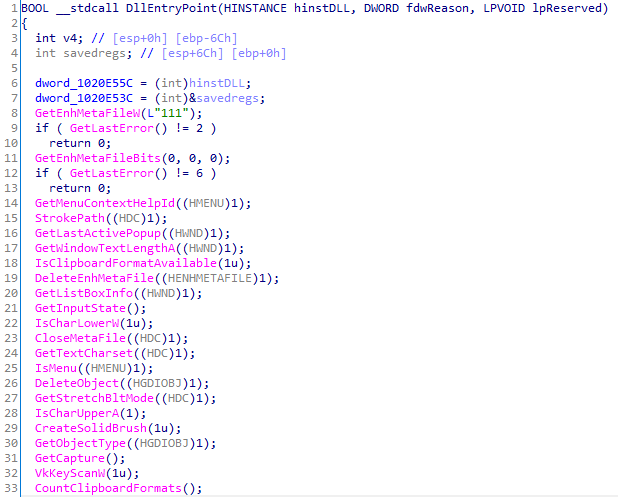

One of the first actions in all packed files is an attempt to open the registry key HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\Interface\{b196b287-bab4-101a-b69c-00aa00341d07} (character case may differ in each particular case) and request a default value. Correct program operation in some modifications of generated code depends on whether these operations are successful.

Interface GUIDs may also differ. Here are some of the possible options:

- {3050f1dd-98b5-11cf-bb82-00aa00bdce0b}

- {aa5b6a80-b834-11d0-932f-00a0c90dcaa9}

- {683130a6-2e50-11d2-98a5-00c04f8ee1c4}

- {c7c3f5a1-88a3-11d0-abcb-00a0c90fffc0}

- {b8da6310-e19b-11d0-933c-00a0c90dcaa9}

The subsequent code obtains the address at which a block of encrypted data is located.

This block starts with a 4-byte number, which stores the size of initial data (those that will be obtained after decoding). By calling VirtualAlloc, a memory block of required size with RWX rights is allocated for decrypted data. Encrypted data is copied to the allocated memory by blocks of X bytes each. In the original file, "spaces" of Y byte length are located between these blocks.

Data is then decrypted by 4-byte blocks:

- Each next block is interpreted as an integer (DWORD).

- Index of the first byte in the block is added to the integer.

- An xor operation is executed between the obtained value and the sum of the index and a fixed key (Z number).

Example of algorithm implementation in Python:

def decrypt(data, Z): index = 0 while index < len(data): dword = struct.unpack("<I", data[index:index + 4])[0] dword = (dword + index) & (2 ** 32 - 1) dword = dword ^ (index + Z) data[index:index + 4] = struct.pack("<I", dword) index += 4

Values X, Y, and Z vary depending on a particular packed sample.

The next stage of extracting payload—the shellcode—is located inside the decrypted data. The shellcode takes control when the decryption ends.

The shellcode dynamically loads functions required for its operation. These functions are listed in the "import table" located at the beginning of decrypted data.

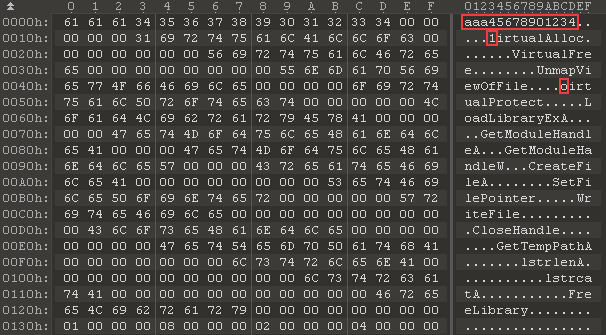

For greater variability, the strings in the "import table" may be partially filled with random symbols. In the example above, the first function name "GetProcAddress" is fully replaced by the string "aaa45678901234", and the names "VirtualAlloc" and "VirtualProtect" are damaged. Right before processing the table, the shellcode restores correct values of all the symbols.

Payload (this time, it is the PE file) is extracted by the shellcode from the rest of the decrypted data. It is encrypted again by the same algorithm as described above. For Z key, figure 1001 is always used.

When the decryption is finished, the shellcode performs reflective loading of the PE file using the functions imported at the first stage.

Obfuscation

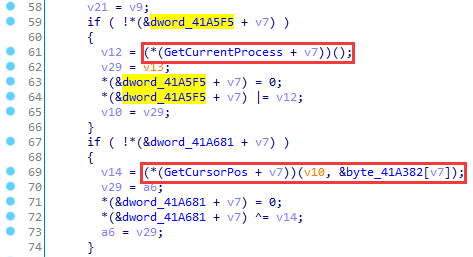

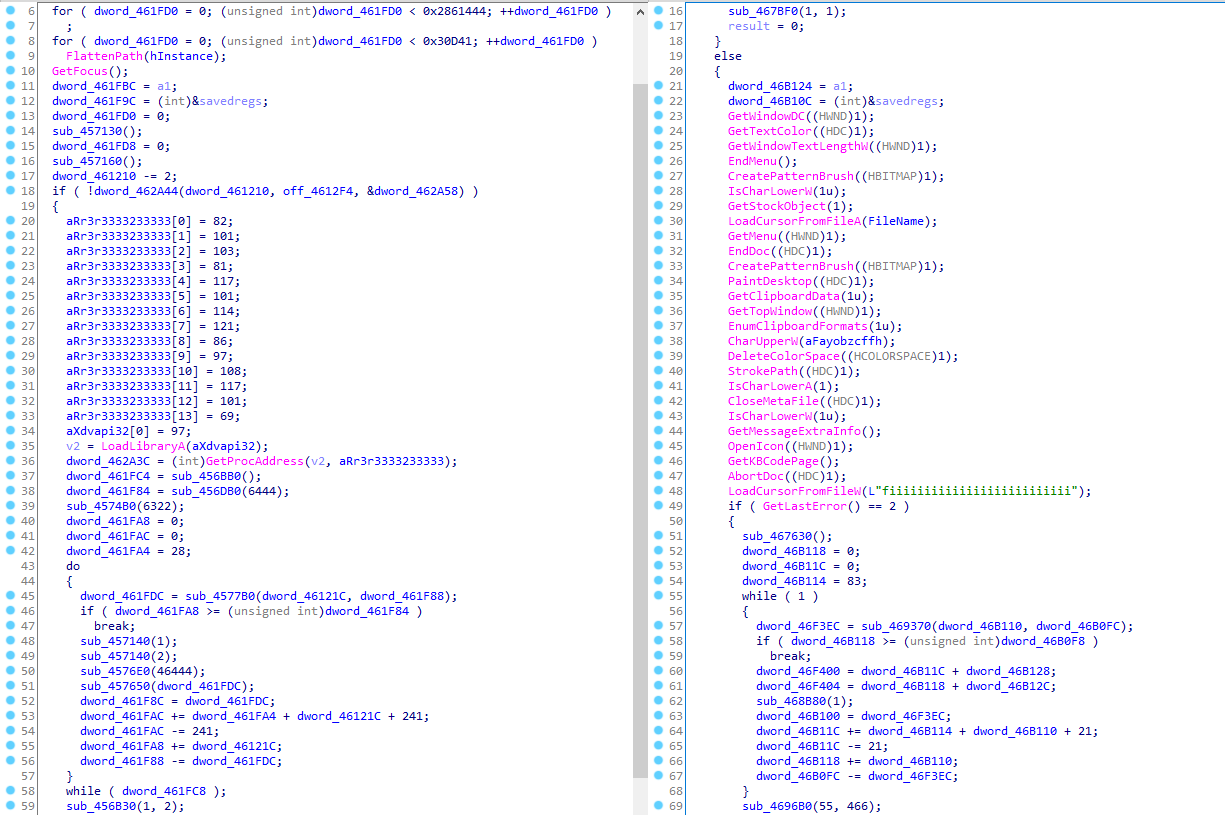

Just like Rex3Packer, HellowinPacker samples call WinAPI functions not related to the main program logic. However, in this case, they are mostly used to complicate behavior analysis and detection in sandboxes. This is also confirmed by the fact that in most cases various functions are called in a row at the very beginning of the program.

An additional effect of the WinAPI use is the impossibility of detection by a list of imported functions and by imphash.

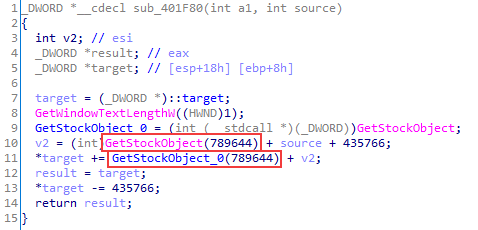

When working with various numeric values, a certain "arithmetic" obfuscation is often observed: necessary constants are represented as sums or differences of other constants (which in some cases equal zero). To obtain constants, WinAPI functions can also be called, yielding predictable results (for example, 0 in case of failure).

An example of such obfuscation is given on the Figure below: the only goal of this function is to assign the value of the argument source to a variable pointed by target. In this case, the output of calling GetStockObject(789644) will always equal zero, as the function was given an intentionally incorrect argument.

Various mutations are encountered at the assembler level as well: inserting junk code, using opaque predicates, calling functions with unused arguments and repeated calls of the functions, and replacing instructions with their equivalents.

Usage

HellowinPacker exists at least since 2014 and has been so far used in various mass malware. Here are only a few examples:

| Malware family | SHA256 |

|---|---|

| Cerber Ransomware | 1e8b814a4bd850fc21690a66159a742bfcec212ccab3c3153a2c54c88c83ed9d |

| ZLoader | 44ede6e1b9be1c013f13d82645f7a9cff7d92b267778f19b46aa5c1f7fa3c10b |

| Dridex | f5dfbb67b582a58e86db314cc99924502d52ccc306a646da25f5f2529b7bff16 |

| Bunitu | 54ff90a4b9d4f6bb2808476983c1a902d7d20fc0348a61c79ee2a9e123054cce |

| QakBot | c2482679c665dbec35164aba7554000817139035dc12efc9e936790ca49e7854 |

The packer has been frequently mentioned in reports by other researchers. The earliest mention we found dates back to 2015. In an article about crypters, Malwarebytes experts analyze malware samples that use HellowinPacker. Later, other researchers referred to it as the Emotet packer (1, 2). In 2020, our colleagues from NCC Group called it CryptOne and described how it can be used to pack the WastedLocker ransomware. According to NCC Group, the crypter was also used by the Netwalker, Gozi ISFB v3, ZLoader, and Smokeloader malware families.

Conclusion

Our example of using the crypters shows us how hackers can delegate responsibilities among each other, especially when it comes to mass malware. Developing malicious payload, protecting it from antivirus tools («crypt»), and delivering it to end users—all this can be performed by completely unrelated hackers, and each element of this chain can be offered as a service. This approach lowers the cybercrime entry threshold for technically unskilled criminals: to conduct a mass attack, all they have to do is to provide a necessary amount of money to pay for all the services.

The packers we described are certainly not the only ones that exist on the market. However, they demonstrate the common features of such tools: as a result of their work, an executable file is obtained with obfuscated polymorphic code of the unpacker and a payload encrypted in some way or another. Mutations in code and reuse of the same crypters make static detection of payload almost impossible. However, since the payload is somehow decrypted to the memory and then starts its malicious activity, behavioral analysis using sandboxes (such as PT Sandbox) allows detecting malware and providing accurate verdicts even for packed files. In addition, it should be noted that packers do not affect the interaction of malware with C&C servers in any way. This makes it possible to determine the presence of malware in the network using traffic analysis tools such as PT Network Attack Discovery.

Verdicts of our products

PT Sandbox

-

Trojan.Win32.RTM.a

-

Trojan.Win32.RTM.b

-

Trojan-Banker.Win32.RTM.a

-

Trojan-Banker.Win32.RTM.b

-

Trojan-Banker.Win32.RTM.c

-

Trojan-Banker.Win32.RTM.d

-

Trojan-Banker.Win32.RTM.e

-

Trojan-Banker.Win32.RTM.f

PT Network Attack Discovery

-

REMOTE [PTsecurity] TeamBot/RTM

sid: 10004412; -

BACKDOOR [PTsecurity] TeamBot/RTM

sid: 10004415; -

MALWARE [PTsecurity] RTM Banker CnC POST

sid: 10000765; -

MALWARE [PTsecurity] RTM.N (Redaman)

sid: 10005556; 10005557; -

MALWARE [PTsecurity] Spy.RTM.AF

sid: 10005468; -

MALWARE [PTsecurity] Trojan[Banker]/RTM

sid: 10004855; 10004875; -

MALWARE [PTsecurity] Win32/Spy.RTM.N (Redaman)

sid: 10003414; 10004754; 10005555; -

PAYLOAD [PTsecurity] RTM.Payload.xor

sid: 10005585;

IOCs (RTM)

| Detection date | Crypter | SHA256 | SHA1 | MD5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19.04.2020 | RTM | a4229a54f76815ac30a2a878eadf275e199c82da657dbc5f3fc05fe95603c320 | ad22ceb309dd30dc769f63174292657fe07f0ced | 80b116708f75de212b49ff994ad8b43e |

| 22.04.2020 | Rex3Packer | 9b88e8143e4452229dac7fdcc3d9281d21390f286c086f09aec410f120dc4325 | f881729f6a5ca6fe80f385a2b0f8583b19214466 | 3965b819eb945a9c0defc746bbc8ed7a |

| 13.05.2020 | HellowinPacker | 43e8ebacfa319ff7d871eef3cc35266cfa7c6f44dd787f27a48311e39727e10f | 8a28b75285409c55d5bbeca62e3819c83c8e663f | afd18be08d135f7bf07007c1c9041126 |

| 28.01.2021 | Rex3Packer (2 layers) | fbf5974daee93bf5a2ed1816a4edbb108ceccb264d3e3f72d0aed268dd45e315 | 2e3352c6341ce57a03aaf2c4fbf484f3a0a4bfe3 | 6e0c8510443586cdc8f84330e447aae5 |