In Q2, the number of attacks increased by 9 percent compared to Q1—and by 59 percent compared to Q2 2019. Significant world events consistently lead to increases in cybercrime, as they provide fertile ground for social engineering attacks. April and May 2020 were record-breaking in terms of successful cyberattacks. This sharp increase was spurred by epidemiological and economic crisis.

Contents

Executive summary

Highlights of Q2 2020 include:

- The number of cyberincidents is continuing to grow. In Q2 2020, we detected 9 percent more attacks than in Q1 2020. Most attacks in the first two quarters of the year happened in April and May, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The percentage of attacks targeting industrial companies has increased significantly. In attacks on organizations, industrial companies were attacked in 15 percent of cases, compared to 10 percent in Q1. Ransomware operators and cyberespionage APT groups are among those who seem to be the most interested in industrial companies.

- Among social engineering attacks, 16 percent capitalized on the COVID-19 pandemic. More than a third (36%) of such attacks were not related to any specific industry, 32 percent targeted individuals, and 13 percent were aimed at government institutions.

- In the cybercriminal world, the demand for credentials is growing. Of the total amount of data stolen in attacks against organizations, the share of credentials has doubled in comparison with Q1. The most common credential theft scenarios include exploitation of web vulnerabilities, phishing emails, malware infection, and bruteforcing of credentials for services on the network perimeter of companies.

- In attacks on organizations, exploitation of software vulnerabilities and configuration flaws accounted for 18 percent, compared to 9 percent in Q1. Internetaccessible corporate network resources are especially attractive to attackers. Criminals have been actively exploiting vulnerabilities in remote access systems from Palo Alto, Pulse Secure, and Citrix.

- Ransomware trojans were present in 39 percent of malware attacks on organizations. A quarter of ransomware attacks on organizations targeted industrial companies. Attackers continue to threaten disclosure of stolen data if victims refuse to pay. LockBit, Ragnar Locker, and Maze operators have joined forces in a so-called Maze cartel to sell stolen data.

- Besides ransomware operators, other threat actors now blackmail victims with disclosure of stolen data and the prospect of fines for violating the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

To protect from cyberattacks, we recommend following our guidelines for ensuring personal and corporate cybersecurity. Whether you continue to work remotely or go back to your usual routine, remember that criminals are always on the lookout for easy prey. They regularly update malicious tactics and techniques so that their actions remain unnoticed in infrastructure for a long time. A web application firewall (WAF), proper incident management, deep analysis of network traffic, as well as use of sandbox and SIEM solutions can help to detect attacks in time. SIEM capabilities provide constant monitoring of infrastructure security incidents, detection of sophisticated attacks on domains, and support for secure remote work.

Statistics

In Q2, the number of attacks increased by 9 percent compared to Q1—and by 59 percent compared to Q2 2019. Significant world events consistently lead to increases in cybercrime, as they provide fertile ground for social engineering attacks. April and May 2020 were record-breaking in terms of successful cyberattacks. This sharp increase was spurred by epidemiological and economic crisis.

Malware attacks

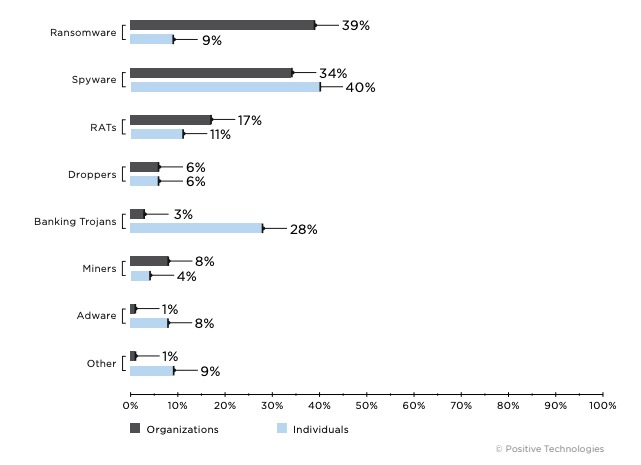

Attackers tend to infect victims with a whole array of trojans, not just a single piece of malware. In one mass malware campaign, criminals delivered LokiBot spyware to victims' computers to steal saved user credentials from various applications. In addition, LokiBot downloaded Jigsaw ransomware to compromised devices. Ransomware and spyware are the most common trojans used in malware attacks. In Q2, they accounted for 39 percent and 34 percent of all malware attacks on organizations, respectively.

Hackers constantly refine their malware by adding new functionality. For example, Valak malware previously was a mere trojan loader. Now it can also be used independently as an information stealer hunting for credentials and domain certificates. Another example is Sarwent. Its developers have added a module that provides remote access to compromised hosts via the RDP protocol. Sarwent enables RDP on compromised hosts and changes Windows Firewall settings to allow connections. It cannot be ruled out that the attackers will sell or rent out such access to other cybercriminals. In May we published an article in which we discussed the illegal sale of access to corporate networks in more detail.

Malware is refined not only to add new functionality, but to incorporate more sophisticated techniques for bypassing protection. For example, specialists from the PT Expert Security Center (PT ESC) detected an updated version of Calypso APT malware. The attackers changed the name of export functions in the main library and set an implausible compilation time (supposedly in 2021). By doing so, they probably were trying to reduce the odds of being spotted by antivirus software.

In Q2 2020, PT ESC detected 13 attacks by the Gamaredon APT group. The group keeps attacking Ukrainian government institutions. They have taken to the technique of remote VBS script loading with mshta.exe. This technique uses built-in Windows tools and allows bypassing AppLocker restrictions on program launch. The script runs after opening of an LNK file from a phishing message.

Industrial companies in the crosshairs

In attacks on organizations, industrial companies were targeted in 15 percent of cases (compared to 10% in Q1). In nine out of ten cases, attackers used malware. About half of malware attacks (46%) involved ransomware, and 41 percent of attacks used spyware trojans.

In our cybersecurity threatscape report for Q1 2020, we talked about new ransomware called Snake that is capable of halting ICS processes. In Q2, we learned about the first victims—Japanese automaker Honda and energy giant Enel Group. Industrial companies were also struck by other ransomware operators, including Maze, Sodinokibi, NetWalker, Nefilim, and DoppelPaymer.

Phishing emails and exploitation of network perimeter vulnerabilities were the initial vectors of attacks on industrial companies. According to Bad Packets, the Sodinokibi operators penetrated the corporate network of Elexon by exploiting vulnerability CVE-2019-11510 in the Pulse Secure VPN.

Cisco Talos discovered attacks on the Azerbaijani energy sector, in which criminals demonstrated interest in SCADA systems related to wind turbines. The attacks started with phishing messages that contained malicious attachments. Among other subject lines, the messages used lures related to COVID-19. The RTM APT group also uses phishing against industrial companies in Russia and the CIS. PT ESC detected 44 malicious mailings by the group during the second quarter of the year.

COVID-19 as a social engineering ruse

In Q2, attackers have been actively exploiting COVID-19 concerns. COVID-19 was leveraged in 16 percent of social engineering attacks. More than a third (36%) of such attacks were not related to any specific industry, while 32 percent of attacks targeted individuals. Government institutions were targeted in 13 percent of COVID-19 social engineering attacks. PT ESC detected attacks involving Chinoxy malware against companies in Kyrgyzstan and Vietnam.

The attackers used the Royal Road exploit builder to create a document exploiting vulnerability CVE-2018-0798 in Equation Editor. The document claimed to contain information about aid from the United Nations to these countries in the fight against COVID-19.

In Q2, PT ESC discovered five phishing campaigns in which KONNI malware was delivered. The criminals lured the victims with information on personal protective equipment for COVID-19.

Malicious emails were not the only technique attackers used to capitalize on the crisis. They also created fake pandemic-related websites hosting malware disguised as useful information, performed business email compromise attacks to steal money, and distributed malicious applications. For example, attackers distributed the SLocker Android trojan disguised as an app called Koronavirus haqida, which means "About Coronavirus" in Uzbek. The trojan locked the screen of the victim's phone, prompting to pay to regain control of the device. Another example is CryCryptor Android ransomware, which masqueraded as Covid-19 Tracer App to attack users in Canada. In most cases, such mobile trojans are distributed via websites, which is why we do not recommend installing applications from unofficial sources.

On the hunt for credentials

Thirty percent of all data stolen in attacks on organizations were credentials, an increase from 15 percent in Q1. Corporate credentials are the most valuable kind of information for attackers. Criminals sell them on the darkweb or use them for further attacks, such as imitating the hacked company to send emails with malicious attachments. Databases with credentials of hacked companies' clients are also in high demand.

Here we will review the most common scenarios of credential compromise attacks performed in Q2 2020.

- Hacking of web resources and theft of credential databases. In Q2, attackers primarily targeted online services, e-shops, and service sector companies. In most cases, they exploited web vulnerabilities or bruteforced passwords to access websites. For example, the Shiny Hunters group posted an advertisement on the darkweb offering the databases of dozens of companies. Among the victims were e-learning platform Unacademy, The Daily Chronicle news website, the Knock CRM platform, and many others. A single database generally costs between $1,000 and $2,000. However, the database of online store Tokopedia, containing information for 91 million accounts, was offered on a darkweb market for $5,000.

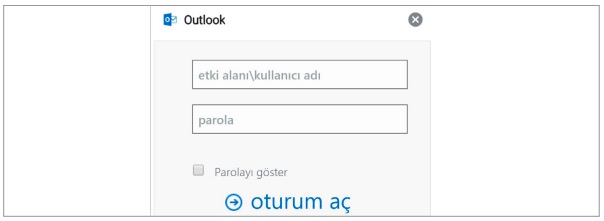

- Phishing emails with links to fake authentication forms. Most often, attackers forge the authentication forms of Microsoft products, such as Office 365, Outlook, and SharePoint. However, at the peak of the pandemic in Q2, they also tried to steal credentials for audio and videoconferencing platforms. In one such case, attackers deployed a phishing campaign against remote employees using Skype, sending them emails with fake Skype notifications. By clicking a link in a phishing email, the victims landed on a fraudulent login page and were asked to provide their credentials. Similar attacks hit users of Webex and Zoom.

- Infection with credential-stealing malware. In most cases, it suffices for employees to merely open a malicious phishing attachment to get their company infected with malware. Lately, in the footsteps of cybergroups, ransomware operators have also started hunting for credentials. In Q2, Zaha Hadid Architects became a victim of Light ransomware. The criminals stole a large number of internal files and compromised employees' accounts.

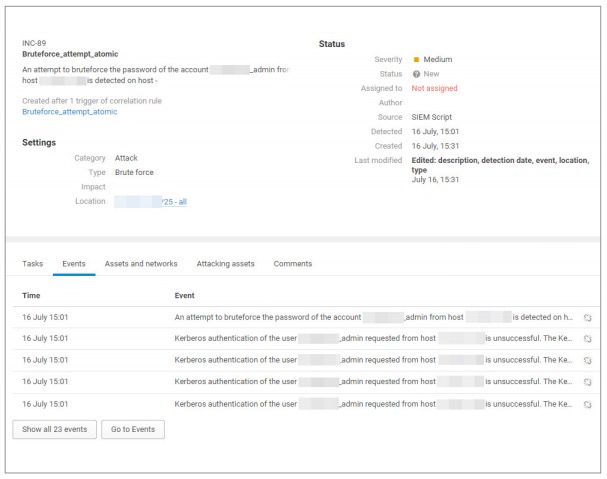

Figure 22. Fake Outlook login form used in a phishing attack against Turkish military vehicle manufacturer Otokar - Bruteforcing of credentials to services on the network perimeter. In the first two quarters of 2020, such attacks have become especially relevant due to the global workforce’s shift to remote work, which made some services accessible from the Internet for the first time. In April, cybersecurity specialists observed an increasing number of attacks across the globe aimed at bruteforcing RDP credentials. In order not to fall victim to such attacks, it is vital to use strong passwords and multi-factor authentication, as well as enable RDP connections only over corporate VPNs. If you do not use RDP, we recommend closing port 3389. Specially configured SIEM correlation rules help to detect bruteforce attacks on corporate remote access systems in time.

Figure 23. Credential compromise incident (MaxPatrol SIEM interface)

Network perimeter resources under attack

In Q2 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and shift to remote work have led to an increase in attacks on vulnerabilities in web-accessible corporate services. As a result, the share of attacks exploiting software vulnerabilities and configuration flaws has increased to 18 percent in Q2 (compared to 9% in Q1). Criminals pursued various goals, from installation of miners to cyberespionage on large companies' networks.

- CVE-2020-11651 and CVE-2020-11652 (SaltStack Framework)

- CVE-2019-19781 (Citrix ADC, Gateway)

- CVE-2019-11510 (Pulse Secure VPN)

- CVE-2019-18935 (Progress Telerik UI)

- CVE-2019-0604 (Microsoft SharePoint)

- CVE-2020-0688 (Microsoft Exchange)

Attackers were especially hungry for remote access systems. As mentioned, operators of Sodinokibi ransomware penetrated the infrastructure of British energy company Elexon by exploiting vulnerability CVE-2019-11510 in the Pulse Secure VPN server. Operators of Black Kingdom ransomware used the same penetration vector in their attack. The Australian Cybersecurity Center has released an advisory on attacker tactics and techniques, stating that exploitation of vulnerability CVE-2019-19781 in some Citrix products has become a vector for breaching the networks of government authorities and private companies in Australia. The vulnerability allows an unauthorized attacker to execute arbitrary code and attack resources on a company's internal network.

In Q2, two vulnerabilities discovered by Positive Technologies experts made the headlines. This time, the vulnerabilities were found in the Cisco ASA firewall. Vulnerability CVE-2020- 3187 allows an unauthorized attacker to perform DoS attacks against a VPN. The second flaw (CVE-2020-3259) allows an intruder to intercept a VPN user's session identifier and access a company's internal network. To eliminate the vulnerabilities, update Cisco ASA to the most recent version.

Signs of compromise of remote access systems include multiple failed VPN connection attempts, attempts to connect to hosts of critical subsystems from the VPN, enabled RDP access on the firewall, and concurrent connections (parallel sessions). To detect such incidents, use SIEM systems with fine-tuned security incident correlation rules.

Once information about a severe vulnerability is published, criminals immediately try to exploit it. Only a few days after announcement of vulnerability CVE-2020-5902, uncovered by our company's expert in the F5 Networks BIG-IP application delivery controller, hackers tried to exploit it. The vulnerability has the highest CVSS score. Note that APT groups may also be interested in exploiting this flaw, meaning that companies that have not yet installed the vendor updates are at risk. To block attacks aimed at exploiting these vulnerabilities, we recommend using a web application firewall (WAF).

Ransomware collaboration

Ransomware is one of the fastest-growing varieties of cybercrime. It has become a common practice for attackers to threaten to disclose the stolen data unless the victim pays a ransom. Maze and Sodinokibi operators were the most active perpetrators of such attacks in Q2 2020. DoppelPaymer, NetWalker, Ako, Nefilim, and Clop are also among the leaders by number of cyberextortion attacks. Some of them, like Ako, even implement a "double extortion" scheme by demanding separate ransoms for decryption and non-disclosure of data.

To sell the stolen data, many ransomware operators create special data leak sites where they publish a list of victims and the stolen information. Others publish the data on hacker forums. LockBit and Ragnar Locker went even further, teaming up with the "industry leader" hacking group Maze. The Maze operators now publish data stolen by other gangs on their data leak site. Together, the gangs have formed the so-called Maze cartel.

However, this is not the only possible collaboration scheme. Ransomware attackers often buy access to victim companies' networks from other criminals. The operators of NetWalker are recruiting affiliates to spread their ransomware by offering a commission on the ransom.

Despite the need to share the proceeds, ransomware owners are still profiting handsomely. In Q2 alone, they reaped millions of U.S. dollars. The University of California San Francisco paid $1.14 million in ransom after an attack by NetWalker ransomware. The Sodinokibi ransomware group hacked American law firm Grubman Shire Meiselas & Sacks (GSMS), which represents a long list of international celebrities. The ransom, set at $21 million, was not paid. The hackers then doubled the ransom and started to offer the data of A-list stars for sale. Criminals claim to have a buyer ready for information about Donald Trump. In May, Sodinokibi held an online auction of the stolen data, the first lot being documents relating to Madonna.

Ransomware owners are not the only ones to demand ransom

Other criminals have quickly caught up with the trend of demanding ransom for non-disclosure. For example, hackers are demanding a ransom from stores in order to not sell the stolen data to third parties. The $500 ransom they are asking is relatively modest compared to what the Sodinokibi operators are trying to extort. Nevertheless, this business model can offer significant profits: database owners are often willing to pay to protect their reputation, while the criminals never run out of potential buyers.

Another cybergroup is breaking into LenovoEMC network-attached storage devices, deleting files, and demanding ransom of $200 to $275 to restore the data. Similar campaigns hit poorly protected MongoDB databases in Q2. Attackers wipe the compromised databases and then, just like ransomware operators, frighten victims with the potential of GDPR penalties unless a ransom of $140 is paid. Note that even unskilled hackers can perform such attacks by using ready-made scripts that allow them to search the Internet for devices with weak passwords or without password protection. It is therefore vital to ensure secure configuration of your systems and use strong passwords and two-factor authentication for critical resources.

About the research

In this quarter's report, Positive Technologies shares information on the most important and emerging IT security threats. Information is drawn from our own expertise, outcomes of numerous investigations, and data from authoritative sources.

In our view, the majority of cyberattacks are not made public due to reputational risks. The result is that even organizations that investigate incidents and analyze activity by hacker groups are unable to perform a precise count. This research is conducted in order to draw the attention of companies and ordinary individuals who care about the state of information security to the key motives and methods of cyberattacks, as well as to highlight the main trends in the changing cyberthreat landscape.

In this report, each mass attack (in which attackers send out a phishing email to many addresses, for instance) is counted as a single incident. The terminology used in this report can be found in our glossary.